The recent death of champion freestyle skier Sarah Burke was nothing short of a tragedy. The world lost a young athlete with limitless potential. Sarah was as comfortable in the X-Games superpipe as she was on the red carpet, and she recently succeeded in getting the sport of free skiing into the Olympics. She was an icon, and her family, her sport, and her nation are still mourning her. That accident brings something to the forefront that we as athletes sometimes try to push out of our consciousness… the sports that we love can sometimes take our lives.

The most disturbing part of Burke’s death is the circumstances. She was performing a routine trick in a non-competition setting, and was wearing proper safety equipment. She died as a result of a severed neck artery that led to cardiac arrest, and doctors said that better protective gear would not have changed the outcome. When events like this occur, they force us to explore the relationship with risk in our own lives, and ask the question: Is it worth dying for?

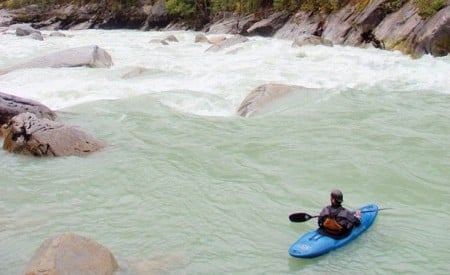

This is a never-ending consideration that adventure sports athletes have grappled with. Climbers want to climb larger mountains, skiers want to ski more difficult lines, and kayakers want to push the envelope of runnable whitewater. These adventurous desires exist inside all of us, and those who possess a larger than normal helping are the ones who are out there pushing their sports to new levels. Climbing Everest, surfing the most massive waves that the planet can produce, or flying a wingsuit is inspiring to the rest of the world, and lifts the hearts of the entire human race to imagine the possibilities.

But where do you draw the line? The inevitable reality of this flirt with the limits is that a few of us may actually find them. Passing away as a result of chasing what you love is something that is embroiled in controversy. You will probably hear as many opinions on this subject as the number of people you ask about it. But fatalities in the outdoors occur for a number of reasons, and are not always the result of negligence or bad decisions.

Sometimes, things just go wrong. One saddening example of this was when professional kayaker Pat Keller lost his best friend on a remote river in British Columbia, Canada. The two were paddling together, and a freak surge sent the young man back upstream into a dangerous rapid after the two had walked around it. Pat was helpless to assist, eventually falling into the river himself from his rescue efforts. He did everything that he could, and then made the walk out of that river all alone to find help.

Nearly ten years later, Pat describes his bittersweet relationship with paddling:

“As I get older, I have to constantly balance those risks with the consequences that I know are there. And oftentimes these days I find myself being more conservative.”

This was an example of a misfortune that could not necessarily have been avoided. The other side of the coin is that the youth seem to have different proclivities with regards to risk today than in the past. Don’t get me wrong: every generation seems to have those opinions about the previous generation, but there are major societal forces at work today that influence the judgment and aspirations of the impressionable youth. Massive corporations are shifting their marketing budgets to enable willing athletes to push their sports to new heights through death-defying stunts. Extreme sports are edging their way into the mainstream via reality TV shows such as Nitro Circus, and people are now turning their attention from other traditional New Year’s Eve pastimes to watching hugely publicized motorcycle, snowmobile, and car stunts. It definitely seems as though “invincible” public figures are glorified, and although these stunts are extensively planned by professionals, the average teenager watching TV may not understand this. It would certainly be difficult to turn down: fame and riches in exchange for pushing your sport to its limits.

Growing up as a whitewater kayaker, things weren’t always like that. As a kid, I was taught a solemn respect for nature and to never push it too far or too fast. Through the course of my life, I have definitely been told that what I do is foolish. I usually let that kind of thing slide, but it cuts a bit deeper when I hear it from family. I do not consider myself to have a death wish at all, and I look forward to a full life in which my contributions to the sport of kayaking are only the beginning of what I have to offer the world.

I do not resent those who say these things to me, because I know that their feelings ultimately stem from fear. It seems as though Americans today fear a great number of things, but the recurring theme is the unfamiliar. Whether it is disease, terrorism or heights, we fear that which we do not understand, and subsequently judge those who don’t fear the same things. That is a dangerous state of mind, and flies in the face of the adventurous spirit that founded our country in the first place. What ever happened to the “go out and skin your knee” mentality that used to exist? Is it possible to have those same experiences via the Internet or video games? One interesting paradox lies in the fact that automobile accidents are a huge cause of death in the U.S., and most of us aren’t filled with dread when we put the key in the ignition every day.

I will admit that I’ve had a few brushes with death during my 15 years of paddling whitewater. One instance in particular could easily have gone the other way. I was paddling the Chattooga River one Christmas Eve, and I managed to pin myself in a slot on one of the rapids of the dangerous Five Falls section of the river. My boat sank deeper and deeper as the force of the current wedged it into an underwater crack, and to my surprise I realized that I could not get out of the boat. The current was pinning me down, and my legs were trapped.

The situation went from a fun, carefree day with friends to a struggle for my life in a matter of seconds, and as I flailed underneath the infinitely powerful waters of the river, I suddenly felt very guilty. How could I put my family through this on Christmas Eve? After my own death became a dire possibility and that thought flashed through my brain, I fought like I’ve never fought before. I very easily came to the realization that I wanted oxygen badly enough that nothing else mattered, and I somehow kicked off my shoes inside the boat, and made every effort to bend my legs sideways to slide out of the boat. In my mind, breaking my legs at the kneecaps was completely acceptable. They bent in a way that they never had before, and I tumbled out of my boat after over a minute of struggling. I couldn’t walk for a week, but I survived.

That experience was a reminder of something that I already knew: the decisions that we make out there can have very real consequences. It also reinforced my determination not to die on the river. I have lived my life in a somewhat non-traditional way… doing my last year of high school by correspondence to travel, taking a year off between high school and university, and making the outdoors and discovery of nature a high priority in my life. If I were to pass away doing what I love, the people who criticized me in the past would say, “it was only a matter of time,” and would take my death as a validation of their own ignorant assumptions. I’ve always wanted to prove that the rat race is not for everyone, and that I can live my life the way that I love without compromise. That may take different forms as I grow older, but I hope that I can feel as though I’m doing that forever.

So how do we reconcile ourselves with this (sometimes unavoidable) risk that comes with our sports? The first step in my opinion is to acknowledge that it is present, and to think very seriously about how much risk we are comfortable with accepting in our lives. This will help to guide every decision in the future, and will be different for every person.

Once this is done, it’s important to become as educated as possible on the many ways to minimize that risk. No matter what your sport, it is important to carry with you the appropriate safety gear and know how to use it. Think avalanche beacons, pin kits, and medical provisions. The aim should always be to turn yourself into the biggest possible asset to your group, and as I write this I can think of a few ways that I will improve my own portfolio of skills this year.

It’s also important to learn any lessons possible from past accidents or tragedies in your field. It is never productive to point fingers after an event like this, but knowledge can often be drawn from these events, and carried with us for use in case of a future crisis.

Finally, when it comes down to the moment, we should affirm that the decision to go is for the right reasons. Taking a calculated risk should not be for the cameras, to impress anyone, uphold a reputation, or because it will create a legacy. Do it because it feels right, and because you are 100% sure that you can follow through successfully. Make decisions for yourself, and follow your gut.

This dialogue brings up a final and pivotal question that seems to be at the heart of this fine balance: On a subconscious level, is this risk and the stark reality of our own mortality part of what draws us to these sports?

Perhaps making life and death decisions and proceeding with confidence is in fact an infinitely purifying and rewarding process. Believing in your own abilities with the ultimate price on the line is something that few people have actually experienced, and that self-confidence can transfer to and carry value in any aspect of life, from business to relationships. There is a part of us that still needs to live the primal life. It is our way of facing the tiger and reacting swiftly and confidently.

Our sports can be dangerous at times, but with humility and a safety-minded approach, they can provide a lifetime of joy.

“The sensations one feels in these activities is comparable to falling in love,” says Keller. “You never know when your heart may break, but until that point, it’s all love.”

For some amazing music from the likes of Great American Taxi and Paul Thorn check out this month’s Trail Mix!