Guidebooks were big in the 90s. Are they still useful today?

Thumb through the pages of any guidebook today and you’ll see bright, high-resolution photographs, topo maps, and even GPS coordinates. But have you ever wondered what it was like before the dawn of the Internet, back when guidebook know-how came by word of mouth from local legends, often scribbled down with pen and paper and shoved into back pockets? Climber Eric Hörst and paddler Kirk Eddlemon know that world well.

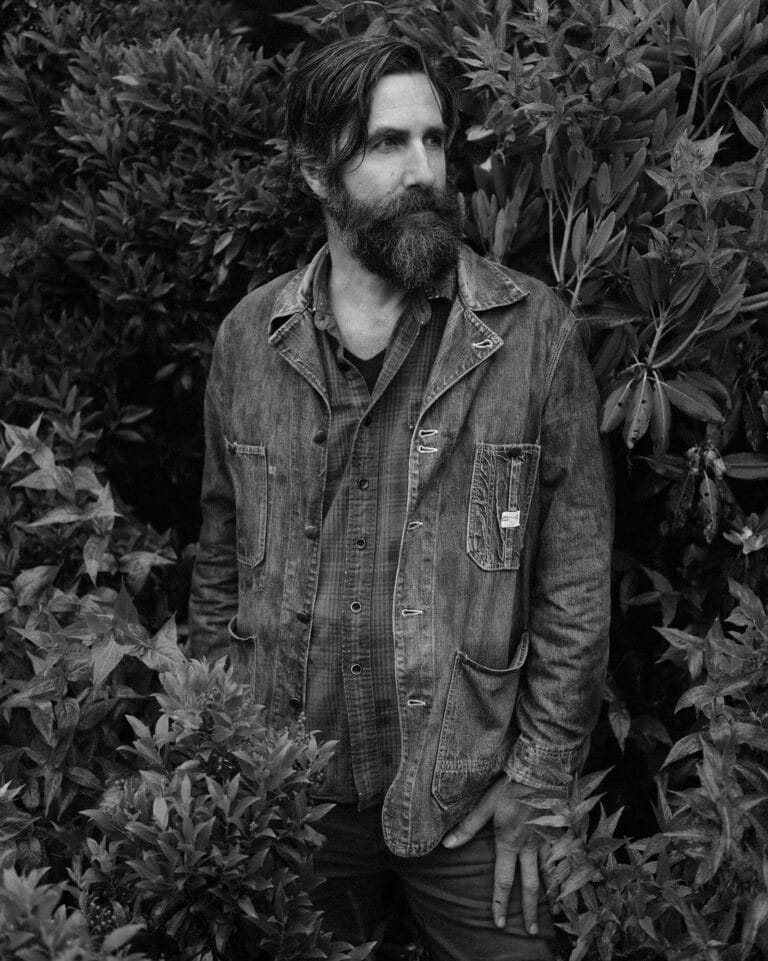

Hailing from Lancaster, Penn., Hörst has been climbing since the early 70s and has put up a number of first ascents in places like the New River Gorge and Old Rag. He’s the author of Rock Climbing Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland, the definitive guide to climbing in the Mid-Atlantic, and has recently written an updated edition to the original guide, which he first published in 2001.

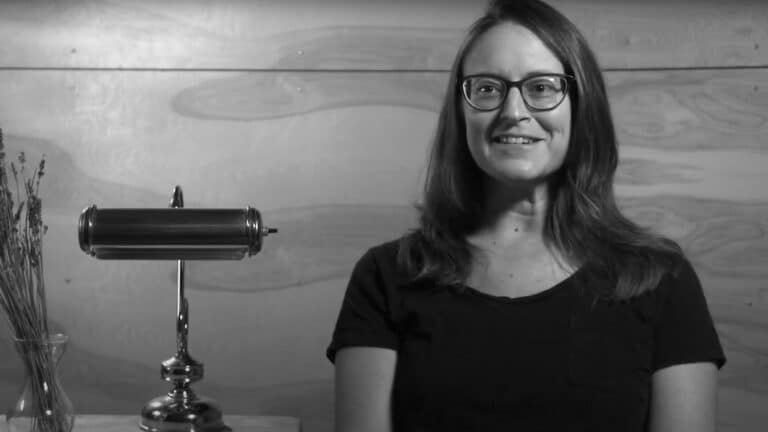

Knoxville born and raised, Eddlemon picked up paddling in the early 90s, and in 2009, he wrote his first-ever guidebook, a comprehensive, two-volume series titled Whitewater of the Southern Appalachians. Hörst and Eddlemon took BRO behind the scenes of a guidebook-in-the-making, a process, I discovered, that is long, slow, and tedious.

BRO: What were the guidebooks like when you first started out?

EH: The earliest guidebook I can think of was Bill Webster’s guide to Seneca Rocks that came out in the early 1970s—it was small enough you could stick in your pants pocket with grainy black and white photos and one or two vague sentences. That was how we rolled back in the day.

Why write a guidebook?

EH: You don’t get rich writing climbing guidebooks, but I’d spent most of the weekends of my young life adventuring around these cliffs and mountains. I know them as good as anybody.

KE: I’ve always had a categorical mind. Ever since I started paddling in the Southeast, I had this unsaid goal of seeing everything that I could, all the rivers and streams, with the notion that that gives me a large-scale understanding of the world around me, which, for me, is grounding.

In the wake of the Internet, what is the future for guidebooks? Do they still have a purpose?

EH: The next frontier is taking guidebooks and making them electronic and accessible by iPhone. I think that’s cool, but what if you dropped your phone? What if your battery goes dead? I don’t think they’ll fully replace a physical paper guide, but it’s going to be fun in the coming years to see how that changes the guidebook industry.

KE: Much like the resurgence in popularity of vinyl in the music industry, the full-color print industry has some security in the fact that despite how high-res your new hipster-approved iTablet is, there’s something indescribable and satisfying about seeing a beautiful image in print or to feel the weight of a volume in your hand.

Some argue that guidebooks exploit local secrets. How do you respond to that critique?

EH: Every guidebook author runs into that kind of thing from time to time. Here’s my policy: if the area is on public land and open to climbing, then it’s fair game to include in the book. And the fact is, with the Internet, there are no secret areas anymore—so why leave an area out of a book when there’s info on the net?

KE: The most valuable reason of all to share our river experiences and information is to establish a record of use, so that in the times when these special places are most threatened, paddling and conservation groups can make empirically legitimized claims, without question. If you hide something precious away so well that the world doesn’t know it exists, are you in danger of losing the very thing you seek to protect? Mankind measures the value of a place based on those who speak the loudest, regardless of true worth, so it is that game that we must play as a small but passionate community of paddlers.

How are your guidebooks different from the earliest ones?

EH: Back in the 70s, you could pretty much bolt just about anything. With guidebooks now, we’ve been able to teach climbers Leave No Trace ethics, proper use of anchors, bolts, and pitons. With the big numbers of climbers and the big impacts as a result, it’s important we be good users and stewards of these areas.

I’m sure making a guidebook is no easy task. How long did it take?

EH: A long time.

KE: Almost five years.

Any memorable moments during the guidebook making process?

EH: I was bushwhacking near Old Rag once for research and ended up totally off the beaten path. I didn’t have GPS or anything. Not a soul was out there, and I kept thinking, one slip and I could hit my head on a rock and be screwed. If I got knocked out, no one would have ever found me. It’s not like I left a breadcrumb trail. I didn’t have a phone. Nothing.

KE: The day I took a ride off Courthouse Falls for a picture. It’s the best picture of Courthouse ever. There’s lush forest, the water’s high, and I’m in a yellow kayak just firing off this thing. In the picture, it looks like I’m going to tuck into the most beautiful landing you’ve ever seen. What you don’t see is me going over the handlebars and landing on my head and my full, 32-ounce Nalgene smashing me in the balls so hard I can’t breathe. That quote “it’s all worth it if you get the shot” was percolating through my mind right then and I just had to laugh through the pain because it was totally worth it.

###

To get your hands on Hörst’s and Eddlemon’s guidebooks, click their respective names and order your copies now!