The Mountain State hosts a world cup and builds a stash of new trails.

West Virginia is on her best behavior.

It’s Saturday morning of the 2021 Mercedes-Benz Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) Mountain Bike World Cup Finals at Snowshoe Mountain Resort. I’m walking the cross-country course with Snowshoe Director of Risk and Business Services and World Cup Event Director Preston Cline. While the elite women make a few practice laps on the course, Cline and I weave through stands of spruce to see how the root-laced track is faring.

Save for a few patches of mud where springs seep beneath the trail’s tread, the course is running dry, at least by Snowshoe standards. Late September weather in the Snowshoe Highlands is always dicey, but the last time Snowshoe hosted the World Cup Finals in 2019, racers were treated to uncharacteristically arid tracks. Two years later, it seems West Virginia is yet again gracing World Cup attendees with her cheery blue skies and hero dirt.

The conditions make Cline’s job, at least in part, a little easier. Hosting the World Cup this year has proven uniquely challenging compared to organizing the 2019 Finals. As if the pressure of shining an international spotlight on Snowshoe wasn’t enough, Cline and his crew have the added stress of safely bringing some 8,000 people from 32 different countries to a rural county of less than 8,000, all during a pandemic. Cline hasn’t slept much in the past week, but for him, it’s worth it.

“It really makes you proud,” he says. “This terrain and these trails that are in my backyard are good enough to bring elite-level riders from all over the world here to West Virginia. That says something.”

That the energy behind mountain biking here keeps building says something, too. Continuing its decades-long track record of hosting elite cycling events, Snowshoe has already announced it will host the 2024 UCI Mountain Bike Marathon World Championships, with more World Cup bids in the works. But while these international events have drawn the most attention from mainstream media outlets, they’re just a small part of a greater mountain bike momentum that’s bringing not just the resort but Pocahontas County to the next level. And to truly experience that, you have to ride it.

It’s quiet at 4,859 feet, the summit of Thorny Benchmark. Sue Haywood and I are pedaling our loaded mountain bikes along the moss-lined singletrack that threads Snowshoe’s dankly forested southern rim. After days of jostling shoulder to shoulder alongside thousands of other World Cup fans, the relative emptiness of the woods feels refreshing. At the base of Snowshoe’s fire tower, we hear the distant din of World Cup crowds erupting into cheer. Unbeknownst to us, American cross-country rider Christopher Blevins had just battled his way to cross the finish line first, something no American man had done in 27 years.

It is the first of five days Haywood—a retired cross-country World Cup rider herself—and I will spend riding our bikes through the International Mountain Bike Association (IMBA) Snowshoe Highlands Ride Center. Initially designated as a bronze level Ride Center in 2019, the Snowshoe Highlands quietly achieved silver level status in late 2020 and is one of only two silver level ride centers on the East Coast.

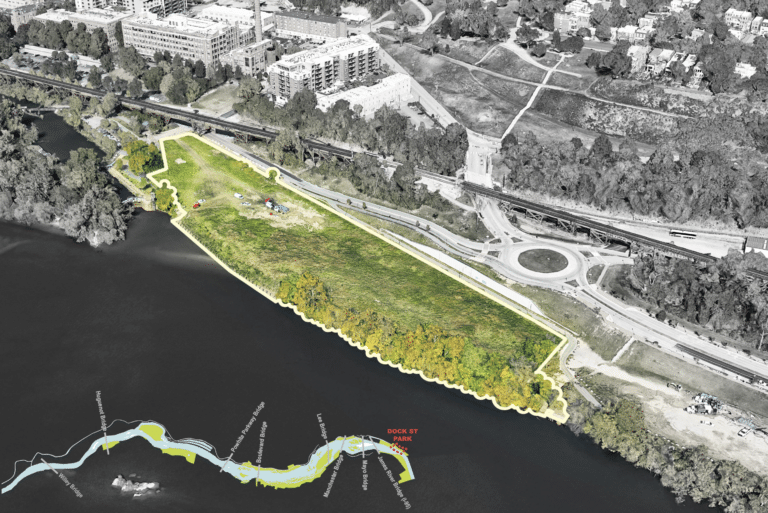

The Snowshoe Highlands Ride Center includes over 375 miles of singletrack, most of which is located in the Monongahela National Forest in Pocahontas County and some in neighboring Randolph County. Our goal is to connect the Ride Center’s major trail systems—the Mower Tract, Greenbrier River Trail, Cranberry Backcountry, and Tea Creek Area—a mostly off-road bikepacking adventure that will cover some 200 miles of rugged high-elevation West Virginia terrain. It is, in effect, a tour through time, linking together Pocahontas County’s logging and mining heritage with its mountain biking past, present, and future.

We begin our bikepacking journey at Snowshoe Mountain Resort. Geographically, the resort is a prime launching point for any adventure in Pocahontas County. Surrounded on all sides by either the Monongahela National Forest or Cass Scenic Railroad State Park, Snowshoe’s backdoor access to thousands of acres of public lands makes it an ideal anchor for the IMBA Ride Center and our bikepacking route.

Our first stop is the Mower Tract, a 40,000-acre chunk of national forest located in Randolph County. From Bald Knob just past Snowshoe’s property line, we descend a fast and loose 20 miles of gravel to the Shavers Fork of the Cheat River before climbing an old horse trail back up to the Cheat Mountain ridgeline. In its past life, the Mower Tract was heavily logged and strip mined. Today, the scarred yet stunning landscape is home to a decades-long restoration project, which includes a budding population of native red spruce and big-toothed aspen, as well as six miles of fresh-cut singletrack.

According to Snowshoe Vice President of Mountain Operations Ken Gaitor, Snowshoe and the Monongahela National Forest are working together to complete a roughly eight-mile trail by the end of summer 2022 that will connect cyclists from the resort through the old rail town of Spruce and to the Mower Tract. The resort has already started crafting the connection by restoring Poleax, an old logging grade on Snowshoe property. The remaining singletrack will be built on national forest land and already has West Virginia Department of Highways grant money earmarked for construction.

Snowshoe intends to use the Mower Tract trail connection as part of the 2024 UCI Mountain Bike Marathon World Championships course, but more importantly, Gaitor says this project is an example of how the resort is pivoting its trail building and advocacy efforts to serve more than just the resort.

“We owe it to the people of this county to be responsible stewards of the land and a community partner that people can rely upon to do the right thing for all of us,” he says. “[Mountain biking] is a community, it’s a culture, it’s not just a resort. If you want that community to grow here, you have to be a good partner.”

After spending a night camping under a full moon on the Mower Tract, Haywood and I pedal south and back into Pocahontas County. Despite calling West Virginia home, Haywood indulges my curiosities. We embrace the tourist attractions, taking time to marvel at the old-growth spruce forests on Gaudineer Knob, lunching at the historic train depot in Cass, cruising along the Greenbrier River Trail at sunset before making camp along the banks of the Greenbrier.

On the third day, West Virginia resumes her normal behavior: stormy and unpredictable. As we climb away from the Greenbrier and up into the Cranberry Backcountry, a thick fog and steady rain envelopes us. We bypass Marlinton to stay off of busy paved roads, but the county seat will soon provide a crucial dirt corridor in Pocahontas County: IMBA Trail Solutions has already flagged 27 miles of singletrack south of town on national forest land, a new purpose-built trail system known as Monday Lick. Construction is estimated to begin here in late 2022, and grant funding has already been partially secured.

From our dry and surprisingly spacious shelter along the Cranberry River, we climb through the Tea Creek Area to the top of Props Run, a classic old-school singletrack descent. It is here that West Virginia finally decides to fully unleash her true nature. Wind lashes the treetops above us. Between the pelting rain and roaring wind, I can hardly hear my brakes squealing as we pick our way down the deadfall-littered descent.

It seems fitting that our fourth day ends where much of the mountain biking in Pocahontas County began: Elk River Touring Center in Slatyfork. For nearly two decades, Gil and Mary Willis hosted the Wild 100 endurance race and West Virginia Fat Tire Festival, both of which brought national renown to the Mountain State.

The Willises greet our mud-splattered bikes and bodies with a genuine warmth and the use of their hose. On our fifth and final morning, we roll out from Elk River with a home-cooked breakfast in our bellies. Before climbing the final pavement stretch back to Snowshoe, we stop at the Linwood Community Library to check out the pump track. Recently built by volunteers and Snowshoe’s bike park employees, the pump track is quaint but well-equipped with a Park Tool stand, a pump, a grill, and a water fountain. Soon there will be a skills area to accompany the pump track, too.

Between the IMBA Ride Center designation and the international attention from the World Cup events, Pocahontas County seems to be having a moment. Eric Lindbergh, president of the local IMBA chapter Pocahontas Trails, certainly hopes so. The challenge now is learning how to capitalize on the momentum in a way that honors the Snowshoe Highlands’ mountain biking roots while simultaneously heralding a new chapter in trails.

“For being out in the woods and not having the population base that everyone else has, we’re doing amazingly well. That’s part of the story,” he says. “It’s slowly happening. It all takes time and money and resources, but that there’s nobody here and we’re able to pull all of this off is pretty cool.”

Interested in the route? Stay tuned to BIKEPACKING.com to learn how you can ride the Snowshoe Highlands 200!

All photos by Jess Daddio