The Geology of Whitewater

As I steered my heavily-patched and atrociously purple canoe towards the infamous “Notch” rapid in the Green River Gorge, I was fairly certain I knew what was coming. I had seen the drop in person before, and had just wasted a week in the office conducting extensive “video-scouting” through the wonder of YouTube. Having driven the same 12 foot monster of a boat through Go Left and Die the previous weekend, I was riding high and felt ready to step up. After all, a 12 foot canoe sporting two sixty-inch airbags can dwarf a lot of river features, and I fully expected to glide right through The Notch without taking on a drop of water. This expectation quickly faded as I dropped off the tongue of green water and into the churning hole below. It felt as if all 12 feet of my boat would be sucked under as water flooded into the boat. I held on to a desperate hanging draw stroke to keep moving towards the salvation of the eddy ahead, maintaining my line as the green tongue crashed onto my stern, tossing the bow into the air and giving me a final push out of main current. As I dragged my boat ashore to dump water before running Gorilla, I was acutely aware that I had underestimated the power of the southeast’s most famous steep creek.

The Notch itself is fairly understated in appearance compared to the crashing, 20 foot high flume of Gorilla just downstream. The challenge it presents to boaters, however, has led more than a few to opt for a “chimp” run, in which a paddler carries around The Notch to run only Gorilla with a guaranteed clean entry. While this respect for The Notch seems inconsistent with its modest height, the energy which the Green River possesses as it funnels into the drop is almost unbelievable and sufficient to require the full attention of the world’s most talented paddlers. The story behind this dynamic feature, and the rest of the Green’s intense rapids, lies in the changes the river experiences as it veers off of the Blue Ridge Plateau and into the Narrows gorge. Most river systems become widen and flatten downstream as they collect more water from feeder streams. A sudden narrowing and steepening of a river channel forces the water to accelerate, focusing its energy to cut into bedrock and ultimately produce a steep-sided gorge. Collectively, the Notch and Gorilla represent the Green at its most powerful, where the channel is simultaneously at its narrowest and steepest. The result of funneling the entire river into such a concentrated jet is violently turbulent water, capable of carving into solid bedrock and tossing boats and their drivers around like features on much larger, high-volume rivers.

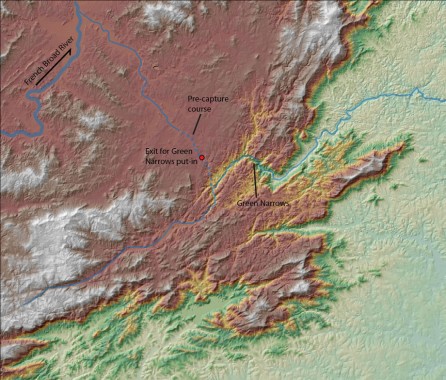

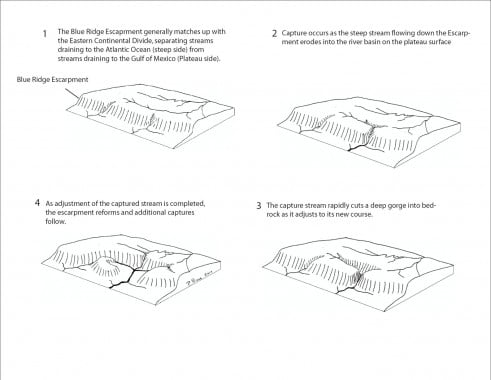

If streams typically lose gradient downstream as they carry a larger amount of water, why does the Green suddenly become so steep while other area rivers, such as the French Broad, lack comparable gorges? The answer can be found at the I-26 exit for Upward Road (and the Green Narrows put-in), where construction work occasionally uncovers rounded river rocks with no river in sight. This is the former course of the Green River, a reminder that it in the distant past it meandered uneventfully across the Blue Ridge Plateau to join the French Broad River. Through a process known as stream capture, a tributary of the Broad River, which flows to the Atlantic Ocean, eroded into the margin of the Blue Ridge Plateau and diverted the Green River off of the Plateau and into a steep course to the Piedmont 1,000 feet below. This sudden change in course profoundly steepened the Green, giving its waters great energy to carve the impressive gorge through which it flows today. The gorge is still growing and advancing towards the Green River headwaters, which still follow their flat, pre-capture course before dropping into the gorge. The whitewater zone of the Green River Gorge will continue to slowly creep upstream through the Green and its tributaries until the entire Green River basin has been eroded down to an elevation that matches the rest of the nearby North and South Carolina Piedmont.

The Green River is certainly not the only southern Blue Ridge stream whose whitewater is the direct result of stream capture by Atlantic River systems. The Linville River was almost certainly the former headwaters of the Nolichucky River prior to being captured into the Catawba River system. The nearby Rocky Broad River, which has excavated the impressive Hickory Nut Gorge, was captured from the French Broad system like the Green. The steep streams of the Jocassee Gorges are also the “victims” of stream capture; the Whitewater, Thompson, Horsepasture, and Toxaway Rivers are all former headwater streams of the ever-shrinking French Broad River system. Even the Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers owe their whitewater to capture events; they are the former headwaters of the Chattahoochee system which were diverted into the Savannah River system. The unusual history of all of these rivers is still reflected in their courses upstream of the steep stretches of whitewater. All of these streams travel relatively quietly through broad valleys before dropping into their rugged gorges; these flat upstream reaches offer a glimpse of what the entire river would have looked like before being captured and steepened. In addition to indicating river history, these long headwater reaches on the Blue Ridge Plateau are essential to producing the boat-compatible whitewater found in the gorges. Most streams of similar gradient to the Green Narrows and other capture gorges occur near ridge crests and are extremely small, lacking enough drainage area to permit descent after even the largest rain events. The captured streams of the southern Blue Ridge, on the other hand, drain large areas before steepening to produce the geologically unusual combination of volume and gradient sought after by whitewater paddlers.

The Blue Ridge Plateau headwaters of the Green and similar streams also raise unique questions about land use and conservation. While the gorges surrounding the whitewater zones appear remote and pristine, much of the upstream land is agricultural and, in some cases, moderately populated. Runoff from farm fields and feed lots, sediment from collapsing stream banks, and roadside litter enter these rivers upstream (and out of sight) of your favorite rapid, potentially harming water quality for stream life and recreational users alike. While most Escarpment whitewater streams have avoided considerable impairment, unchecked development and irresponsible land use make the future of these outdoor playgrounds uncertain. While the flat headwaters of the Green and other captured streams may not receive much attention, we must remain aware of the incredible beauty that lies downstream in order to protect the geologically unique whitewater resources here in the southern Blue Ridge. Rapids like The Notch and Gorilla offer are already stressful enough without added worry over water quality.