David Horton is begrudgingly beloved. He wouldn’t have it any other way.

The 67-year-old ultrarunner-turned-race-director is the mad scientist behind some of the ultrarunning community’s most reputable races, the Mountain Masochist 50 Miler (which he no longer directs), Holiday Lake 50K, Promise Land 50K, and Hellgate 100K. Over the course of his three-decade-plus ultrarunning career, Horton has logged a dizzying number of achievements—over 160 ultras, speed records on the Appalachian Trail (1991) and the Pacific Crest Trail (2005), and the third-fastest time of the Trans-America Footrace (1995), just to name a few.

By all appearances, Horton is a glutton for punishment. Even open heart surgery and a total knee replacement hardly slowed him down. Runners aren’t sure whether to admire the man or fear him. Or both.

It’s no wonder then, that adversity is part and parcel of his ultras. Impeccably organized yet relentlessly brutal, Horton’s races are relics of a bygone era, a time when race applications arrived by post and grit, not glory, made a runner great. There is still no online registration for Hellgate 100K, and should a runner DNF or fail to run her best, she should expect shame, not sympathy, from David Horton.

It’s nearing 9p.m. on Friday, December 8, 2017. Nearly 200 runners, crew members, and volunteers are crowded into a room at Camp Bethel in Fincastle, Va. In just two hours, the entire room will caravan to the start line of the 15th annual Hellgate 100K. Horton is midway through his pre-race briefing when someone asks about the course records. He turns to Sarah Schubert, the 2016 women’s winner.

“Prove me wrong. I don’t think you’ll beat the record. Even if someone beats you, I don’t think they’ll beat the record. Amy Sproston is a better runner than you.”

There’s a split second of uncomfortable silence. I’m tucked in a corner behind Horton with some of his students from Liberty University. Stunned, I wait for the “just kidding” or the punch line that will break the ice. But it doesn’t come.

“He likes to be inflammatory,” Schubert tells me a week later. “If people want to do well in Horton’s races, it takes a different type of person. You certainly don’t want to come to his races expecting to be coddled, either by him or the course.”

Horton continues to dole out tongue-in-cheek jabs that teeter between playful and crass. No one is spared. The assistant to medical director Dr. George Wortley is “a good woman, but a little strange.” George Plomarity, the Patagonia representative, “weenied out, wussed out,” and DNFed at his first Hellgate. Even I find myself at the root of some ridicule. “Daddio? That’s a terrible last name. Are you married yet? Well good, that means you can still change it.”

When it comes to Hellgate though, Horton’s ruthless candor is the least of the runners’ problems. There’s plenty to dread about this one-of-a-kind point-to-point ultra: the 12:01a.m. start at an unpredictable time of year, leaf-covered technical trail, the real threat of frozen cornea (dubbed “Hellgate Eyes”) and sleep-deprived hallucinations, 12,000 feet of climbing, and those nasty “Horton miles” that turn this 100K into a befitting 66.6 miles instead of the standard 62. Just crossing the finish line at Hellgate is a commendable feat. Many runners race Hellgate once and never return. But sitting in that room at Camp Bethel are five runners who have shown up every year since 2003, in respect of but not unfazed by Horton or Hellgate. They are the Fearsome Five.

[nextpage title=”NEXT PAGE”]

Actually, it’s just the Fearsome Four at the moment. Ryan Henry from Carlisle, Penn., “is a dear friend of mine,” says Horton, “but he’s late for everything.” The others are folded into the crowd of runners, and he calls each one out in classic Horton fashion.

Jerry Turk from Guilford, Conn., but originally the south of England, is “the Yankee.” Darin Dunham of Huntsville, Ala., will be “the first of the Five to drop out” from the streak. Aaron Schwartzbard from Washington, D.C., “runs either here or here,” says Horton, holding one hand high above his head and the other stretched low toward his feet—Schwartzbard won Hellgate back in 2007 with a time of 11:28:13, but he’s also had years when the course took him well over 15 hours. “Maybe it’s those sideburns.”

“That’s not usually the kinda thing that comes up in most pre-race briefings,” Schwartzbard tells me later. “There are people who are highly turned off by the David Horton Show, because he does tend to say things that are not necessarily polite. With anything he says, it’s not entirely serious, but it’s not entirely joking either, and there’s something to be said for that level of honesty. We live in this Instagram Facebook culture where everyone’s like, ‘Go get ‘em! You’re great!’ and Horton’s not afraid to call it like it is.”

The final of the Five, Jeff Garstecki from Columbia, Md., somehow eludes Horton’s banter. He and his wife Tammie are lingering near the back of the room when Horton dismisses the runners. It’s Tammie’s first Hellgate, and I can almost feel the anxious excitement emanating from her.

“We’re going to try to squeeze in a nap, but I don’t know how much sleep I’ll actually get,” she says.

Jeff, on the other hand, exudes a levelheaded ease about him, which surprises me when I learn of his injury.

“I have three degenerative discs in my back,” he says. “If the race had been last weekend, I wouldn’t have been able to run. I couldn’t even walk to the bathroom at Thanksgiving.”

After 14 years of running Hellgate, Garstecki and the other Fearsome Five know better than anyone how different the race can feel from one year to the next. Out there, everyone faces his own demons, be they changes in physical fitness, recent injuries and illnesses, or life stressors. But it’s that, combined with unpredictable weather, which can really make or break the race.

In 2013, it snowed, then rained, and never got above 40 degrees. Two years later was the hottest Hellgate to date with a high near 80 degrees. And in 2016, temperatures reached a record low for the race at eight degrees. Runners couldn’t drink their water fast enough and ran for miles between aid stations with useless, frozen hydration packs.

“If the weather is particularly challenging, it levels the playing field quite a bit,” says Jerry Turk. “It doesn’t matter if you are a racing snake in your mid twenties, if you have to deal with bitterly cold, freezing conditions and that’s something new to you, then in my mind, I’ve got a little bit of an edge because I’ve seen it before.”

That first year in 2003, runners ran on two feet of snow under a perfectly full moon. The visibility was so clear, most of the racers went without headlamps. Two years later, in 2005, the ice was so bad runners could hardly find traction on the parking lot, let alone the trails. Garstecki, who fell more times than he could count, bonked, became hypothermic, and nearly dropped at Bearwallow Gap over two-thirds of the way through the course.

“I remember it was freezing out, right, but I felt so hot, so I was taking off my clothes. My plan was that I was going to lay down in the snow until the next runner came behind me. I didn’t lay down, I kept walking, waiting for that next runner, but nobody reached me before I got to the next aid station. I spent 45 minutes to an hour just getting warm by the fire. My legs were so bloody from the ice scratching my legs. I managed to finish, and I got the best blood award that year.”

More than the elements and the strenuous physical output, Hellgate has been a mental game for Schwartzbard. He nearly won the race in 2003, back when nobody knew the course and certainly nobody knew him. A marathoner at heart, Schwartzbard was surprised to find himself alone and in the lead for 45 miles. He nearly started congratulating himself on his performance when another runner sailed past and pushed him into second.

“I really had it in my mind that I just might make it. I had my eyes on the winner’s jacket, and then at the end to be passed like that, even now when I get to where I was passed that first year, I have this dark feeling like there’s some sort of haunting there. It was such a deflating moment that hung over me for awhile.”

In 2004, Schwartzbard again placed second. A year later, he slid to eighth. By then, he had given up hope of ever winning Hellgate. In 2006, he ran his slowest time to date at 16:10:51. But in 2007, when he showed up to register the Friday night before his fifth running of Hellgate, he was surprised to see Horton had seeded him number one.

“That was a little bit awkward. The guy who had won Hellgate the year before was number two, and usually you always seed the previous winner as number one. Horton is not hung up on etiquette, though. That fall I was in really great marathon shape, but that’s very different from being in trail shape. Still, he realized I had more fitness than I recognized in myself.”

Sure enough, like some self-fulfilling prophecy, Schwartzbard won that year, thereby lifting the heavy cloud that had been hanging over him since 2003.

[nextpage title=”NEXT PAGE”]

It’s 10p.m. now, and though a few of the runners are sitting around the room making small talk with their crews, most are trying to catch some shut-eye. Outside, rows of red taillights idle in the night. Exhaust clouds the parking lot as runners crank the heat and stuff themselves under steering wheels for a few fitful minutes of sleep.

It’s a crisp 22 degrees and snow is in the forecast. The park service has closed access to the Blue Ridge Parkway. Crews and volunteers are scrambling to adjust the affected aid stations and support. David Horton is sitting by the fireplace, figuring out the final details of drop bag and firewood deliveries. Despite the last-minute change in plans, Horton is practically spilling over with excitement, his mouth twitching with a mischievous glee.

“It’s like Christmas, this race to me,” he says. “The build up, the build up, then the weekend and YES IT’S UNREAL. But then boom. It’s over. It’s depressing after it’s over. It’s depressing after Christmas is over.”

It’s obvious Hellgate is Horton’s favorite child. He flat out tells me so, but I can see it in his eyes and hear it in his voice, the way he dotes on his dedicated volunteers, the runners who pour heart and soul into the race, even the Camp Bethel setting which makes the whole event feel like part summer camp, part family reunion.

Horton is first and foremost a champion of hard work. He knows the fulfillment of giving something your all and succeeding. He also understands the complexities that emerge when you give 100% to any endeavor and still fall short. In 2008, Horton had to abandon his speed record attempt on the Continental Divide Trail after a brutal first day. A year later, on day six of his supported speed record attempt of the Colorado Trail, Horton ran four miles off course and started to experience severe swelling of his appendages. He knew he had to call it quits.

Though he’s since had to switch from running to cycling due to residual knee problems, Horton still regards races, and more generally life-in-motion, not as yardsticks for any sort of physical prowess but as reminders in our ability to persevere in life, no matter the physical, mental, or spiritual obstacles that may befall us.

“This is our race. We’re in this together. I ran my first marathon three weeks before I got my doctorate. Which do you think mattered more?”

At 10:50p.m. on the dot, a train of vehicles pulls out of the parking lot at Camp Bethel. When the entourage arrives 45 minutes later at the Hellgate Trailhead, the northern terminus of the Glenwood Horse Trail, there’s a flurry of activity as racers make last-minute adjustments to their packs and shed their warm jackets once and for all.

As the clock ticks ever closer to 12:01a.m., they reluctantly leave the warm cars behind and head to the starting line. The air quivers with adrenaline. After the singing of the National Anthem, Horton begins the countdown.

“Five minutes until 12:01!” he hollers through his megaphone. “One minute…and five…four…three…two…one…go!”

Headlamps stream through the blackness beyond. The racers howl into the night, like wolves on a hunt. Soon, the only sounds are that of Hokas and Altras and Salomons shuffling through the leaves.

“It’s game time,” says Horton. “Let’s roll.”

Horton climbs into the passenger seat of a beige FJ Cruiser, which promptly takes off down the road. I follow behind, occasionally catching glimpses of the runners’ headlights bouncing through the trees. Throughout the night, we drive up steep and narrow gravel roads from aid station to aid station, stopping for just a few minutes to check in and cheer on the head of the pack.

Around 2a.m., it starts to flurry. Driving in the dark with the wind whipping snow, I lose all sense of direction. My eyes struggle to focus. Up until the start, I had been riding on the runners’ high, but the sleepless night starts to wear on me. I try to shake it off. I’m not running 66.6 miles, after all.

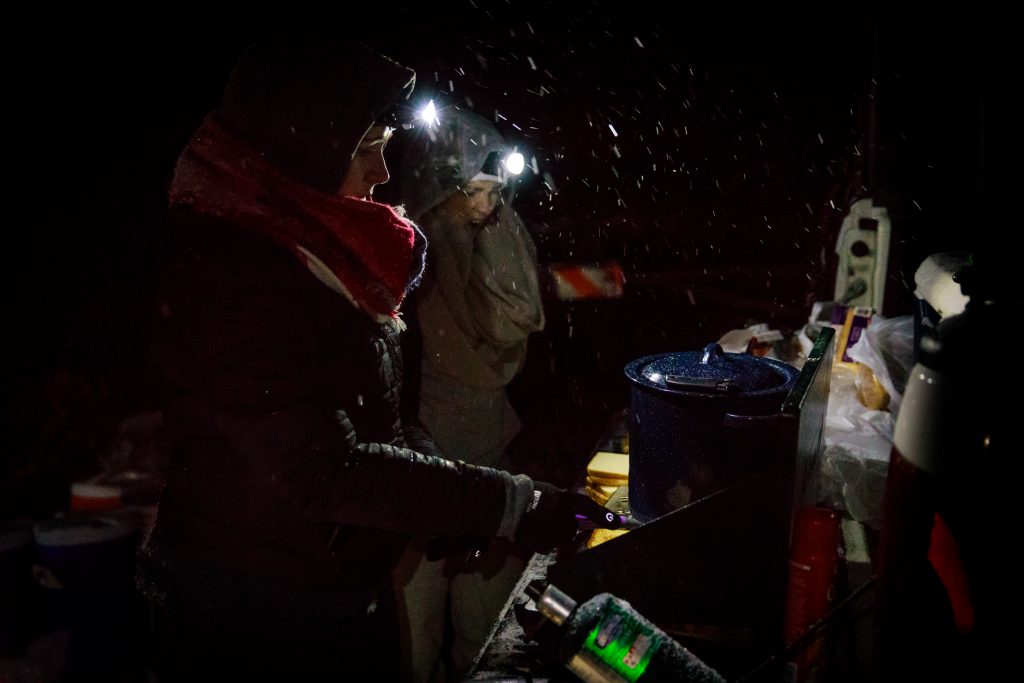

It’s still dark out when we pull into aid station five, Jennings Creek, the breakfast aid station. The location is just a few miles short of the halfway point on the course and marks a milestone for most runners as the beginning of daylight. It’s only 4:30 in the morning now, but the place is alive with life. Christmas music blasts from a speaker. Someone dressed in a reindeer suit tends to a roaring fire. Decorative lights line the final runway into the aid station, beckoning runners from the depth of night.

Before long, the first runners stumble in looking a little shell-shocked, a little tired, but no worse for the wear. They dig through their drop bags, refuel, and are back on the trail in a matter of minutes. And so are we.

By 5a.m., the snow is falling in heavy, fat flakes and accumulating fast. Horton adds some streamers at a road crossing where the snow has covered the trail and we zip up to one last aid station before heading to Bearwallow Gap. Dawn is just beginning to break when we arrive at the parking lot. Horton quickly lays out the drop bags and helps assemble the aid station.

Just after 7:30a.m, we see the first runner emerge from the woods. It’s Matt Thompson, a runner with Crozet Running. Horton hustles over to him and hands him a Coke. Thompson takes a couple of sips and starts to close the bottle, but Horton interjects.

“Drink the whole thing. You need it.”

There’s frozen blood smeared under Thompson’s left eye, but he hardly seems to notice. He doesn’t linger long, and soon, he’s climbing up past the aid station, head down, pushing into the wind and snow.

Over the next four hours, we continue to greet and cheer and feed runners as they wearily materialize from the notoriously treacherous section Sophie Speidel, a 10-time Hellgate finisher herself, christened “The Devil Trail.”

“It’s almost like Russian roulette out there,” Jerry Turk told me before the race. “You have no idea what’s beneath those leaves because the layer of leaves is quite thick. You’re just running along hoping and praying you’ll be able to react quick enough and not fall flat on your face.”

[nextpage title=”NEXT PAGE”]

Aaron Schwartzbard is the first of the Fearsome Five to reach the aid station. He’s in a surprisingly cheery mood given the current course conditions. It’s no longer snowing, but the wet snow is deceptive and makes the leaves slicker instead of adding traction.

“Well look who it is!” says Horton upon seeing Schwartzbard. “You’re doing alright. It must be those sideburns!”

“You wanna stroke them for good luck?” says Schwartzbard.

Schwartzbard takes his time socializing, filling his hydration pack, and crushing a few pierogies. The cold eventually starts to take its toll, and he grabs a pierogi for the trail and hikes it out of the gap.

We stick around long enough to see Sarah Schubert come into the aid station. She’s still in the top five women and moving strong, but the leader Hannah Bright is a good 20 minutes ahead.

“This year was hard for me,” she tells me after the race. “I had just run a 100-miler a month before and Horton knew that. My legs and body weren’t quite ready and he recognized that, but he wasn’t demeaning about it. He was like, ‘You found your limit. You can run this race, sure, but if you want to race and do as well as you know you can do, that’s too short of a turnaround.’”

Camp Bethel is quiet when we return. It’s close to 11a.m., and Matt Thompson is expected any minute. His family waits in the room where, just 14 hours earlier, the entire starting field of 140 runners had been seated at the pre-race briefing.

In the back of the room, volunteers organize a spread of snacks and beverages. Multiple pots of coffee are at the ready. Another volunteer is seated at a table with a radio in hand, coordinating pick-ups for runners who dropped out or didn’t make the time cutoffs.

Horton bursts into the room, still brimming with enthusiasm despite going full-steam for over 24 hours without any sleep (or coffee, for that matter). He’s just been to where the trail pops out onto the road, the final stretch, and says Thompson is 10 minutes away.

There won’t be any records broken on this 15th running of Hellgate 100K, but when Thompson, accompanied by his sons, finally drags himself across the finish line with a time of 11:22:09, Horton is beaming with pride. He wraps Thompson in a warm embrace, the kind of hug that a father might give one of his own on graduation or wedding day.

“Everyone knows they’ve done something when they finish this race, every finisher, every year,” says Horton. “They can’t take it for granted that they’re going to finish. You have to earn it every time.”

For the next seven hours, Horton greets every single runner at the finish line. After nearly 17 hours of running through the night and day, and into the night again, Darin Dunham is the final of the Fearsome Five to arrive at Camp Bethel. It’s his fastest time in seven years he tells me, and at just under 17 hours, his time qualifies for the Western States lottery. Like Darin, Aaron, Jerry, and Ryan all have relatively uneventful runs for their 15th Hellgate. But Jeff Garstecki felt every mile at the end.

“Personally, I think it was one of the harder years, definitely in the top three or four as far as toughest conditions go,” Garstecki tells me a week later. “The Forever Section was when I started feeling bad and I just never came out of it. We’ve all had that. But as bad as I felt throughout this race, there was no thought of stopping or quitting. The streak keeps me going.”

And so, the streak lives on, even if “it’s really just an accident that I keep signing up,” according to Ryan Henry. How long will it last?

“25 sounds like a nice number,” says Dunham. “And if there are five of us in 10 years, that’ll be awesome, but at the same time, if one of us doesn’t finish, I won’t shed a tear.”