Richard Ayers, an operations steward with DCR, starts a fire with a drip torch. Photo by Ellen Kanzinger

Prescribed burns are being used for land management and habitat restoration in the Southeast.

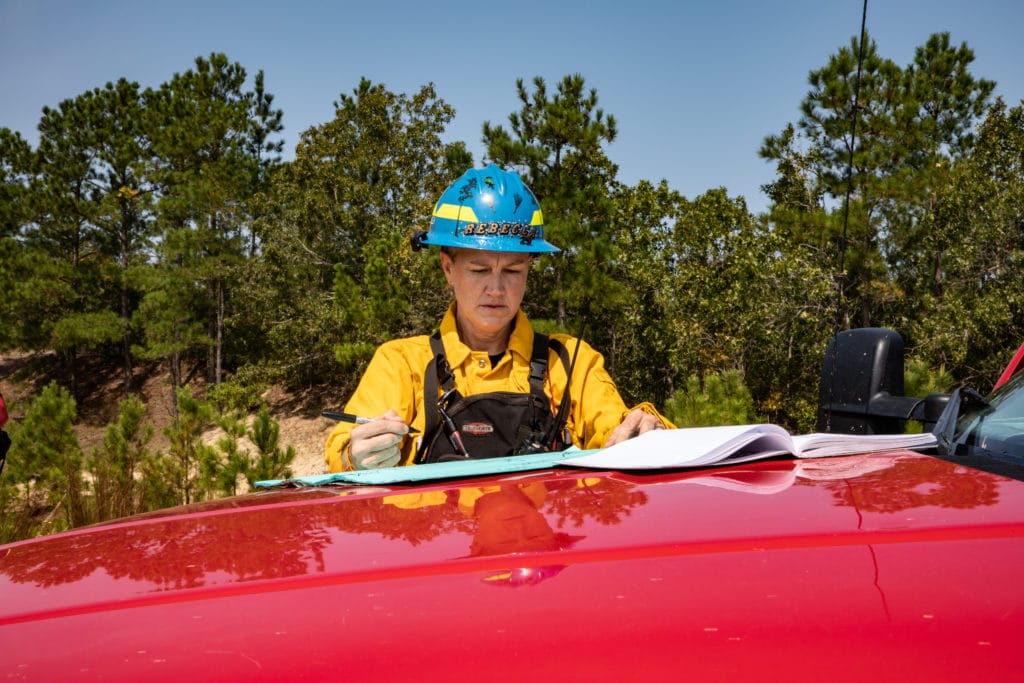

Rebecca Wilson gives the go ahead, watching the drip torch crew as they start to make their way across the preserve. As the day’s burn boss, she’s responsible for making sure everything goes according to plan at the South Quay Sandhills Natural Area Preserve in Suffolk, Va.

The burn starts out slow, a few flames rolling across the eastern edge of the unit as the crew tests the weather conditions and makes sure the fire does not cross the swampy phragmites at the property’s boundaries. Once the test is complete, the drip torch crew proceeds to make their way back and forth across the preserve until the 43-acre burn unit is covered in flames and enveloped in a haze of smoke. You can hear the crackling, snapping, and roaring as the fire burns different types of vegetation.

As a fire manager, Wilson oversees prescribed burning in the eastern region for the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s (DCR) Natural Heritage Program. DCR and other government agencies and private organizations use fire in a variety of ways to manage natural areas.

Before a prescribed burn can even happen, the individuals and agencies involved put together a detailed burn plan that addresses all of the safety and biological factors that might affect the fire. “We actually write a prescription, like a doctor would write a prescription for a medication, for what we want the parameters to be when we burn,” Wilson said. “By the time we strike the match, 80 to 90 percent of my job is already done.” The parameters include things like wind direction, temperature, fuels, relative humidity, days since rain, and the number of people and equipment needed.

All of these factors affect how the fire will act on the landscape and need to be approved at multiple levels before any fire can be used. The goal of a prescribed burn is to minimize extreme fire behavior and ensure the smoke has somewhere to go. If on burn day even one of those factors is outside the range detailed in the prescription, the fire is called off until another day when the conditions are right. “My job is literally dependent on which way the wind blows,” Wilson said.

The burn plan also includes control lines, barriers like a waterway or road to stop fire from spreading beyond the burn unit. If the property doesn’t include any of those nearby, land managers will put their own line in using a tractor, mowing, chemicals, or rake. “We have a lot of different options, but we like to start with what is already on the landscape that will limit the spread of fire naturally because those are always going to be your best bets,” Wilson said. “It’s way better to use a creek than it is to rely on you manipulating the landscape.”

Only then, once a plan is put in place, neighbors are contacted, and conditions are right, does the fire start.

The Tree That Fire Made

Before Europeans sailed across the ocean and forced the Indigenous Peoples off their land, longleaf pines covered around a million acres in Virginia. By 2000, when scientists started to get serious about restoring the species to its native habitat, less than 100 acres remained.

In addition to serving as eastern fire manager, Wilson is also a longleaf pine restoration specialist. Fire is her number one tool for bringing the tree back. “That’s the one you go to every time,” Wilson said. “We use fire to get rid of the vegetation, like you would a plow or a disc. We use fire to prune the trees and get rid of any fungus or disease in the leaves or needles so that they regrow more healthy. We use fire to add nutrients to the soil. There’s this whole spectrum of things that the only way to do that at the landscape level is with fire.”

Because it evolved in a fire-adapted environment, the longleaf pine is also better equipped to survive a wildfire than other tree species. When it germinates from a seed, it produces long needles above ground that look like a clump of grass while developing a strong underground root system. “The loblolly pine makes a miniature tree,” Wilson said. “If you have fire in the first couple of years of growth of that tree, it’s likely to kill it because it has a very small root system. It puts all of its energy into above-ground growth. You can easily burn that off. Whereas [with the] longleaf pine, if you get fire in the system while it’s in that grass stage, instead of it harming the trunk of the tree, it just affects the needles. I like to say it’s just having a bad hair day.”

After storing all of its energy underground, the longleaf pine will then bolt from the grass stage to about four feet tall in one season. “It’s not the kid who eats all his Halloween candy that first night,” Wilson said. “It’s the kid that saves it.”

At the South Quay Sandhills preserve, Wilson and her team are using fire to preserve Virginia’s last remaining natural stand of longleaf pine. The day’s prescribed burn will help clear the property of logging byproduct left from the previous owner and allow the longleaf pine to thrive without other competition. Seeds collected from the site will be used in longleaf pine restoration across the commonwealth.

Fire is critical to the survival of other species in the region. The table mountain pine relies on fire to melt its cones and release the seeds. Without fire, it doesn’t regenerate very well. In restoring these various pine savanna ecosystems, fire managers are also helping to provide habitat, cover, and food for a variety of species which rely on these habitats to survive.

Interagency Training

Prescribed burning is no small task. To execute a safe burn for all involved, including the wildlife and neighbors to the property, it requires a lot of equipment and personnel. Stephen Living, a regional lands and access manager for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), uses fire to restore habitats for wildlife. One of the department’s current focuses is restoring the open pine savanna habitats for species like the endangered red cockaded woodpecker.

“It’s more than any one agency can really do on their own at the scale that we need to be working at,” Living said. “The interagency partnership we have allows us to fluidly share resources, personnel, equipment, and time. There are a limited amount of days that it’s appropriate to burn so by coming together in this collective, we can prioritize the different agencies’ goals and try to get as much of it done as we can.” In Virginia, this partnership includes DCR, DWR, Department of Forestry, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Services, and The Nature Conservancy. When DCR is burning, it’s not just DCR personnel and equipment on the scene managing the fire.

Those involved with prescribed burns are required to pass a work capacity test, a demonstration of physical capabilities, and take a refresher course to be certified as a wildland firefighter every year. Instead of each agency conducting their own training, members train together so that everyone’s on the same page when out in the field. “We try to take it to the next level and really offer some practical training so that it doesn’t just become a rote checking the box every year,” Living said. “This is challenging and risky so we have an obligation to really approach it from the standpoint of giving people the tools to be successful.”

In addition to reviewing the basics every year, everyone must also practice deploying a fire shelter. “We hope we will never be in a situation where we have to do that,” Wilson said. “But we make sure that we train annually so that it’s not only what we know to do, we have some muscle memory that backs it up. Because it’s a really intense situation, wildfires and prescribed burning, it’s very easy to lose focus and concentration. There’s a lot of adrenaline that you need to learn how to control.”

Not All Fire Is the Same

The prescribed burn of the South Quay Sandhills Preserve stands in contrast to the devastation seen out west this fall. Wildfires of historic proportions destroyed millions of acres and displaced thousands of people in California, Oregon, and Washington as smoke from the flames polluted the air from coast to coast.

There are a variety of factors that determine how frequently and intensely a fire burns on a landscape, including the type of vegetation in the area and climate patterns. The Southeast’s landscape is long adapted to fire through natural ignition from lighting and traditional Indigenous burning practices. But decades of fire suppression almost completely removed fire as a natural tool from the land.

“It’s a weird thing to wrap your mind around but when you take the fire out of the system, you’re actually making the fire that eventually comes much worse,” Wilson said. “What the Europeans did was basically cut down all of the big trees and take fire out of the system. You went from having these wide open forests where fire would have occurred frequently and just poked around on its own and gone out eventually to having these landscapes that were more extreme when they did have fire. That is a product of fire exclusion.”

With frequent, low-intensity fires, you’re continually getting rid of above-ground mass so that it doesn’t accumulate as fuel for a potential wildfire. “Not to single out Smokey Bear, but Smokey Bear was part of the climate that all fire is bad,” said Claiborne Woodall, DCR’s western fire manager. “Even Smokey changed his message about 10 or 15 years ago. It went from ‘only you can prevent forest fires’ to ‘only you can prevent wildfires,’ drawing the distinction between wildfires and prescribed fires.”

Although we don’t have the same level of wildfires as the West Coast, events like the Great Smoky Mountains wildfires of 2016 demonstrated there are still dangers in this region. Those wildfires burned over 17,000 acres in eastern Tennessee, including parts of Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg. “It really brought back home the risk that we have here in the East due to decades of fuel accumulation and fire exclusion and the risk that poses to adjacent communities,” Woodall said. “Virginia is never going to be California as far as severity of wildfire risk and the flammability of the fuels, but we have our own version of it.”

It’s also being predicted that climate change will likely exacerbate fire conditions in the Southeast and across the country as the frequency and intensity of storms increases and rising temperatures extend the fire season and drought conditions. With the future in mind, prescribed burning is currently one of the primary tools used in the region to reduce potential wildfires through proactive fuel mitigation.

Prescribed burns help clear the land of fuel to reduce a wildfire’s impact. Photos by Shannon McGowan

According to Gary Wood, the Southeastern regional coordinator for the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy, it’s part of an initiative born out of the FLAME Act of 2009 that’s attempting to create fire-adapted communities, maintain resilient landscapes, and respond to wildfires with regionally specific solutions.

“Even though everybody hears about the fires in the West, we actually have, annually, more than 50 percent of the ignitions of the overall wildfires,” Wood said. “So we actually have more fires. They just happen to be smaller because we can get to them quicker. And we do so much more prescribed burning here than what is done in the West.”