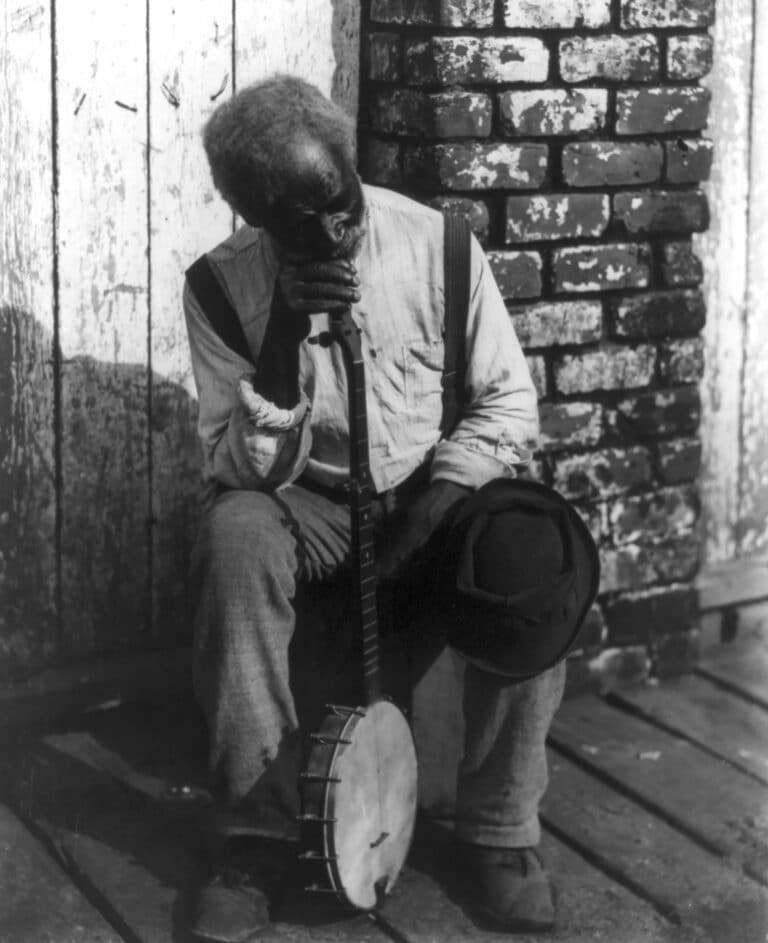

A cyclist explores the 47-mile Swamp Fox Passage in South Carolina. Photo by Mike Bezemek

Biking Through the Francis Marion National Forest in South Carolina

It wasn’t love at first sight with the Swamp Fox Passage. The first time I stepped foot on the Palmetto Trail in Francis Marion National Forest, I was chased to my vehicle by a cloud of mosquitos. Half joined me inside for a slap-happy bloodletting—I mean getaway—along US-17.

“After the first frost,” suggested the attendant at Steed Creek Ranger Station. It was almost November, but a hot October had kept biting insects at summer levels.

Temps came down during the next month, but my wife and I had trips planned through December. We returned in January for a short day-ride on the adjacent Awendaw Passage. It’s a scenic bluff-top trail above a creek, which starts at the Intracoastal Waterway and ends seven miles later at the US-17 trailhead. The ride was mostly flat, muddy in spots, and semi-buggy, yet intriguingly scenic through matchstick pine forest and blackwater wetlands. This convinced me to give the 47-mile Swamp Fox Passage another try.

While planning the longer trip, I started reading about the forest’s namesake Francis Marion. He was a Revolutionary War hero whose exploits were far more unconventional than odd desires to mountain bike through a swamp.

In the late 1770s, the thirteen states were fighting for independence against the British Empire, and Francis Marion was a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army. After reaching a stalemate in the North, the British shifted their strategy to capturing the South. In 1779, the British fleet was preparing to invade Georgia and South Carolina. One target was Charleston, where Marion was stationed.

During a rowdy officer’s party, the drunken host locked the door so no one could leave until everyone got smashed. Since Marion didn’t drink, he supposedly took the advice literally and jumped out a second-story window. He broke his ankle upon landing and was evacuated from the city with those unfit for duty. By early 1780, Charleston was captured by the British, whose forces soon occupied the entire state. Meanwhile, a recovering Marion was limping between hiding spots in the swampy region that became the national forest—a situation which led to Marion organizing a ragtag militia as a last hope for rebellion in the Low Country.

The Swamp Fox Passage runs through the heart of the national forest. Initially, I considered bike-packing the 47 miles as an overnight, but, like Marion, I sometimes leap before looking. Finding little information, I decided to reconnoiter the passage with three out-and-back day rides. I targeted early February. Of course, just days before starting, a massive storm swept up from the Gulf. Luckily, it skirted inland, dropping only 1.5 inches of rain on the forest.

I called the forest service info line, hoping to check conditions. A guy at Seewee Visitor Center said he’d checked for updates this morning.

“The trail is good to go,” he said. “No flooding.”

The next morning, I rode away from US-17 on a bed of longleaf pine needles. It was cold and gray, but otherwise a great day. This 13-mile segment of the trail was mostly a single or double track elevated atop old logging traces. The surface was typically packed soil and sand, often with roots, sometimes grass, and mostly dry with occasional puddles. I pedaled through pine forests and cypress swamps, crossed narrow bridges over tidal blackwater creeks.

For a Saturday, there weren’t many people. A few hikers, including one sunburned retiree wearing nothing but a black speedo. He kindly re-tucked all items as I rode past. I saw one horse-riding group. A church group near one of several trailside camps. I met mother and son backpackers, with the elder encouraging the younger, who was training for the Appalachian Trail.

Reaching my turnaround, I rode through a few inches of water near Steed Creek Road. An ominous sign, which I forgot while returning to my truck. Driving home, I called my Chattanooga buddy.

“I think I found a mellow, winter-weekend bike-packing route.”

Two days later, I parked at Witherbee trailhead and rode into the central forest. After seven miles of puddle-pocked straightaways, the trail dropped into a sunken bog near Turkey Creek. It was 10 miles of slogging from there. We’re talking standing water and thick mud. Brief pockets of spongey spoil atop high ground felt like pavement. I was relieved to have my fat bike—occasionally, I went off-trail through the forest. I crossed creeks and swamps on elevated beams and logs, walking some, riding others, and falling off more than enough. A few makeshift causeways sunk below water level from my passing weight.

The scenic Francis Marion National Forest features matchstick pine forests and blackwater wetlands. Photo by Mike Bezemek

Reaching Steed Creek Road wearing soggy shoes and half the swamp, I returned on the network of sandy roads. While navigating this workaround, I discovered that palmettoconservation.org’s maps excellently delineate the trail, but the roads are off. The forest service’s 2012 revised topo map is better with roads, less precise for trails. As a backup, most parts of the forest have data service.

I gave the trail a few days to dry out and went back to reading about the revolution. For two years in the early 1780s, Francis Marion led a small volunteer militia in a guerilla campaign against much larger British forces. Marion relied upon local intelligence, creative thinking, and covert ambushes. They burst from the forests and freed captured Americans, disrupted British supply lines, and won countless skirmishes against enemy patrols. Then they retreated into the swamps and hid. During one unsuccessful pursuit, according to Simms, British adversary Colonel Tarleton coined a nickname.

“This damned Swamp Fox, the devil himself could not catch him.”

Without any major battles, Marion’s so-called “Brigade” fought the British Army and Loyalists to a prolonged draw. This kept them engaged in South Carolina and unable to reinforce their northern forces, allowing George Washington’s Continental Army to win the war in the north. Even today, historians credit Francis Marion—a 5’2” 100-pound militia leader who limped with a crutch, disliked direct conflict, and slept in swamps—with saving the American Revolution.

Before my final ride, I re-watched the 2000 film “The Patriot.” Mel Gibson’s character Benjamin Martin is loosely—loosely—based upon Marion. Not including the double-fisting muskets and ax-throwing parts.

After four days, I returned with bike to the swamps. Driving to the Lake Moultrie trailhead, something was amiss. It hadn’t rained in a week, but the Santee River was flooding, and water was ponding in meadows. I’m new to this area, and I suspected I’d made a critical mistake.

Sure enough, the trail was flooded. The storm eight days before had dumped further inland. With the region being so flat, it took a week to reach a saturated Low Country. Not wanting to surrender, I rode about a mile. Well, more like waded.

Out of curiosity, I called the visitor center. The guy said he checked for updates that morning. No flooding on the trail. But my soaked shoes told a different story. I later found out, there are never any updates for the Swamp Fox Passage. Thus, proceed cautiously. Ride between the first frost of fall and just after the final frost of spring. Avoid when the Santee River is flooding.

The Swamp Fox had defeated me. For now. Fifteen miles of trail were under water. But unlike the British Empire, I’d be back.