The Author Discusses His New Book, A Shot in the Moonlight, and His Search for Answers on Hiking Trails

For most of his life, author and journalist Ben Montgomery was not a hiker.

An Oklahoma native and college football player at Arkansas Tech University, the Tampa-based reporter for Axios says he had gone on two long walks in his entire life. The first, as a kid, after getting lost in his hometown of Moore, Okla.; the other, when Montgomery and a few friends set out to hike Big Bend National Park, post-college graduation, but got lost.

While researching the story of Emma Gatewood for his second non-fiction book, Grandma Gatewood’s Walk, which won a 2014 National Outdoor Book Award and became a New York Times best seller, Montgomery began walking sections of the Appalachian Trail. “When I started doing big miles on the A.T., I just fell in love with it,” Montgomery says.

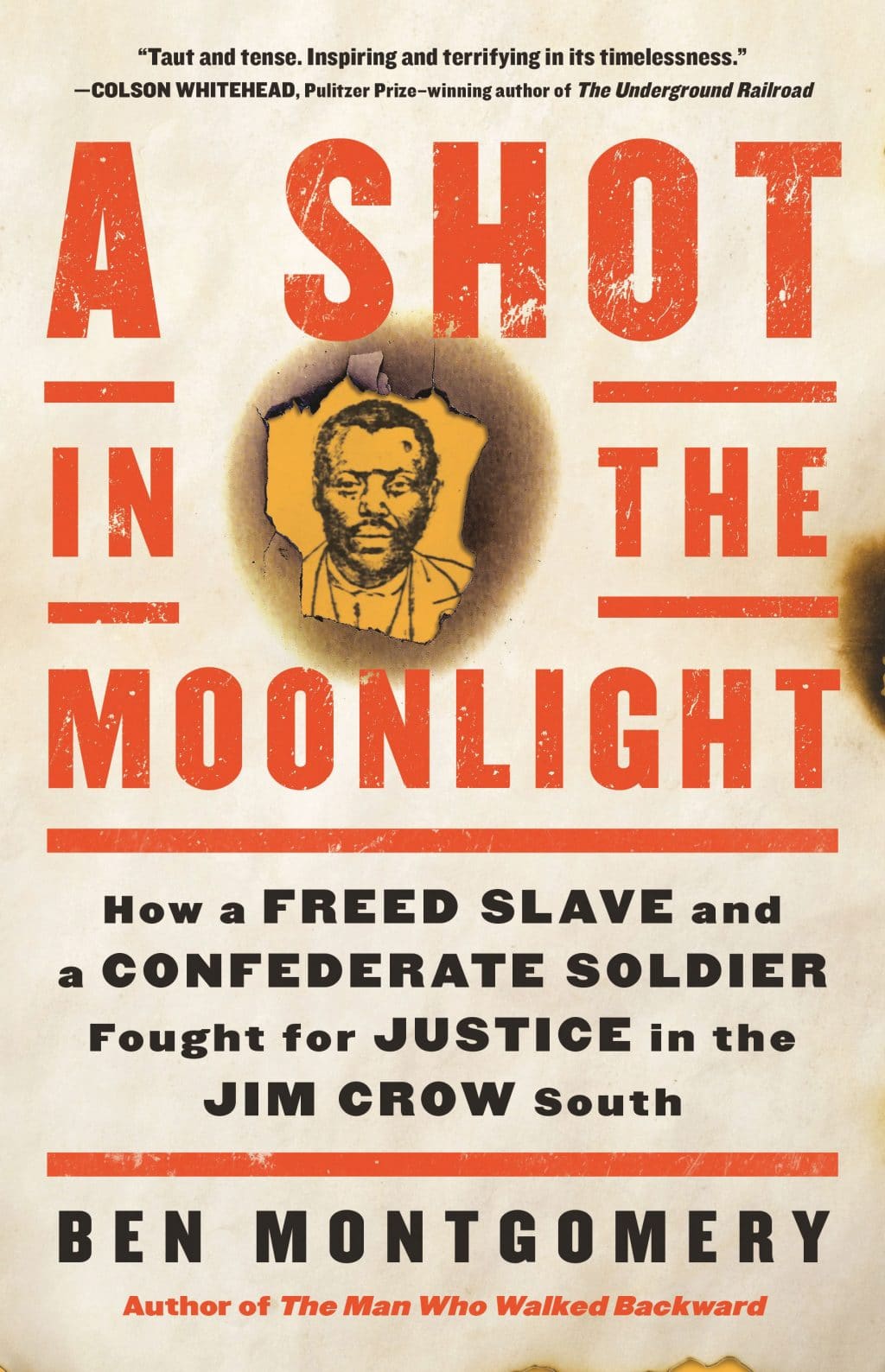

Montgomery’s newest book, A Shot in the Moonlight, was released in January. Readers from Oprah Winfrey (via her O Magazine) to Colson Whitehead have raved about the book and its timeliness in conversations about racial justice. The riveting read shares the story of a freed slave, George Dinning, who shoots a member of a mob gathered outside his home, flees, is imprisoned, and eventually works with a white lawyer and former Confederate soldier, Bennett H. Young, to fight for his freedom as well as an end to laws of oppression and racism. The story—deeply reported and sharply told by Montgomery—also explores our country’s continued reckoning with racist laws and systems

BRO caught up with Montgomery just before the book’s release, talking about his writing projects and how his love of hiking has shaped him and his family.

BRO: All of your books dive into historical explorations. What is it that you love about this genre?

BM: I come from a long line of Oklahoma storytellers who would just sit around and talk. Chief among them was my Granny Montgomery, this itty-bitty lady, who would sit with me on the back porch swing when I would spend summers with her. She would tell me stories—about her dropping a wrench out of a treehouse on her sister’s head; or when she was a little girl and a dog came by and snatched a piece of pie off her plate and she flicked her fork at the dog, and as soon as she did, the dog turned around and the fork stuck in his nose, and he dropped the pie and ran off. There’s so much [history] out there that’s never been revisited. A treasure chest of stuff just waiting to be discovered. It can satisfy the sort of desires that I have to tell very particular stories, if I can look in the right place.

BRO: Your books often focus on those forgotten by history. How did that start?

BM: I was working at the St. Pete Times on the enterprise team, working almost exclusively on the series about the Dozier School for Boys, a terrible reform school in north Florida. As I was reporting that, I learned about this unsolved lynching that 5,000 people participated in in 1934, the lynching of Claude Neal. I started working on that as a side project. Long story short, we ran a story that I remain very proud of called Spectacle: The Lynching of Claude Neal. I tried to sort of solve this case. Somebody should’ve, no one ever did. That wound up getting a lot of attention and in front of a literary agent named Jane Dystel—she represents an [expansive] client list, including Barack Obama. She called out of the blue, and it was like my dream unfolding before me. She said, ‘I like what you’ve written, I like your style, but do you have any book ideas?’

I sent her three little pitches, and one was Grandma Gatewood, who’s a distant relative of mine. I didn’t know much about her, but I knew no one had given her serious biographical treatment and there was a lot unknown about her. My books have come out every two years: 2014, 2016, 2018, and early 2021.

BRO: How did you discover the story of A Shot in the Moonlight?

BM: This one was very purposeful. I had been doing a project for the Times about police shootings in Florida, and there’s a big racial disparity, as there is everywhere, of people shot by police. Forty percent of people shot by police are Black when Black people make up only 15 percent of the population. We had a public records projects, we had like 831 total shootings and 40 percent were Black. Reading through these one after the next, this tragic story of a young Black man, most of the time, killed by police. I was longing for a story that didn’t end up in tragedy for a person of color.

I went to the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery [Alabama] and I started wondering, what names are not on these boxes? They have these coffin-sized metal boxes that you start walking through until eventually you go down underground, and they are suspended above you. You feel the gravity and enormity of that issue in the US. 4,400 people were lynched between the Civil War and 1950. I started wondering, ‘who made it that we didn’t know about, whose names aren’t on the boxes of the victims?’

BRO: You started hiking as research for Grandma Gatewood’s Walk. What is your relationship to hiking now?

BM: I’ve become a person who hungers for the outdoors. It’s almost like I’ve organized my life around being outdoors—hiking especially. The most recent trip we took was about 70 or 80 miles on the Florida Trail this past January. It was all wading, most of the time in water up to our knees. You can only walk about one mile an hour, it’s that’s strenuous. It was glorious, being in the swamp. Just some gorgeous country.

This past summer, we were able to fly to Alaska where we hiked the K’esugi Ridge Trail, about 30 miles outside of Denali State Park.

BRO: What is it about hiking in particular?

BM: I have fallen in love with nature and with being away. I feel like we are so encumbered, so burdened/put upon by our technology, which we thought was a thing that would help us. I’m sitting at my desk, talking to you here [on ZOOM], I have an external monitor, a work computer, my cell phone. I have two voicemails since we’ve been talking and four text messages. We have become so burdened by this connectivity, that the only way I can relax is to get far away, out of signal zone. To set everything I have—all the Slack, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, email, phone—to ‘I’m Away.’ That’s what I say on my outgoing things: ‘I’ll be in the wilderness for a while. Please give me patience.’ Then I can go, and it feels so good to not worry about responding to people.

And I like sleeping on the ground. I wish I could sleep on my little accordion mat every night.

On longer hikes, I like the idea of really testing myself: how much do I have now? It’s a way of measuring where I am, the agility and physicality and pain tolerance and a marker of stage of life. I feel like the trail sometimes reminds me that I am alive. And tells me how much time I have left.

BRO: What is your family’s relationship to hiking?

BM: We get to know each other in ways we never would at home. You get closer. You fight sometimes, but you build your relationships in pretty amazing ways.

I lost my son in March [of 2020], and we still have some questions about his death, but we’re pretty sure it was a suicide. He was 11. It came as a complete surprise. And it was myself, my ex-wife, and my two daughters all together finding him at the same time. So, it’s been a rough 10 months. That was March 3rd, Super Tuesday, so I just want to acknowledge that because I feel like I’ve answered a couple of questions as, ‘me and my daughters,’ but Bey was with us until March of last year.

I thought [getting into the woods] was a method of building resilience against all of the challenges that these kids are facing. In the same way Emma Gatewood escaped to the outdoors to get away from her abusive husband, these guys can escape to the outdoors to get away from the fear of gun violence in their schools, which they live with every day; they can get away from the toxicity of social media. They can get away, lately, from the politics—you can’t be alive without absorbing some of that, even if parents try to protect kids from those things. The violence of the news and the flow and intensity of their world, coupled now with a pandemic. I thought it would help them build that kind of resiliency.

That’s part of the reason that Bey’s death was so surprising to us. We are no closer right now to understanding what he was dealing with than we were that day, so maybe there’s truth to that, but maybe not. As a person whose son probably took his own life, that sounds like a shitty answer. That was my hope, you know what I mean? But I don’t know.

And it’s weird how the trail sort of answers the thing that you’re looking for. I was using All Trails to find a couple of 40-mile trails that we could hike that were within a reasonable drive from each other. I didn’t know about the Resurrection Ridge Trail, but it followed the Resurrection River over the Resurrection Pass Trail and ended in a place called Hope [Alaska]. I was like, ‘thank you, trail, for giving us this very in-your-face thing that was not what we expected.’

BRO: Is there one hike you’d love to do that you have yet to tackle?

BM: I’ve been looking at this trail that runs the length of New Zealand, Te Araroa. 1,865 miles—the length of the country’s two main islands. The cool thing is it goes through like four different climate zones, it goes along the ocean and through farmland and prairie and then up into mountains.

BRO: Have you ever hiked the Blue Ridge sections of the A.T.?

BM: Two summers ago, we started at Rockfish Gap and hiked all the way to Harper’s Ferry. Me and the kids and my girlfriend at the time and my nephew—it was a fantastic time. It was 190 miles, and we were doing probably 12 miles a day.

The summer before, with my three kids, including my then-nine-year-old son, we did the southernmost 260 miles, starting in Hot Springs, N.C., and walking to Springer Mountain, Ga. We had some really long days because some shelters were closed for bear activity. One day, I think we had to put in 17 miles, which was really tough for the nine-year-old.

BRO: Have you hiked the whole A.T.?

BM: I have yet to do the whole thing. I’m not even close. I think we’ve done a total of about 400 miles, and if you couple that with my day excursions, it’s probably 450, tops. I would love to, though. I think about it every year.