To feel the highs of bikepacking, you have to endure the lows.

“I feel good, I feel great, I feel wonderful.”

Lindsey smiles, but doesn’t respond. We both are toasted from the day’s 70 miles of hard riding. With 30 miles still to go—all uphill—even talking feels like a waste of precious energy. I put my head down and pedal on.

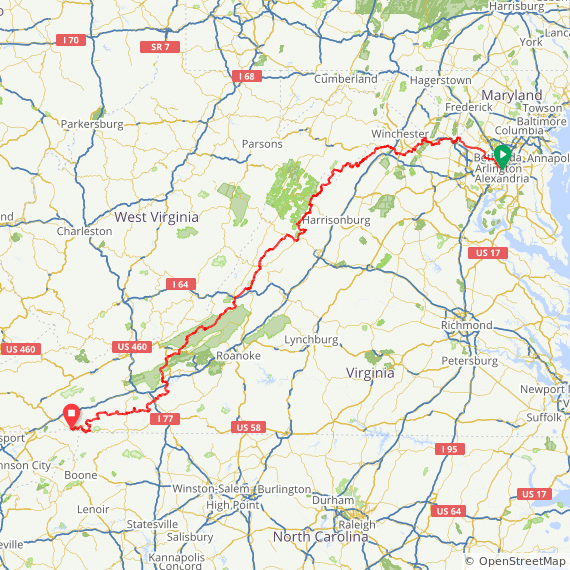

It is day seven of our trip down the TransVirginia Bike Route, a 550-mile mostly gravel route that begins in Washington, D.C., and ends in Damascus, Va. Our eyes are set on the Comers Rock Campground high up on Iron Mountain. If we reach it tonight, we’ll finish the route tomorrow.

As we climb away from the New River south of Pulaski and into the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area, a bone-deep fatigue settles over me like a weighted blanket. Every pedal stroke feels labored. I chug along, so sluggish I might as well be riding through wet concrete. Maybe it’s snack time. Or maybe it’s the prior day’s 9,000 feet—and the past week’s 37,000 feet—of climbing sapping the strength from my legs. Either way, I cram a handful of gummy bears in my mouth.

I feel good, I feel great, I feel wonderful. This refrain—borrowed from Bill Murray’s character Bob Wiley in the 1991 classic “What About Bob?”—has been our mantra from day one. Day after day I recite it to myself, timing the cadence of the words with the rotation of the cranks and the (annoyingly) persistent and rhythmic click-click of my creaky bottom bracket. It’s a silly, paradoxical sort of chant, but its hypnotic effect distracts me from the attrition in my limbs.

Of course, this is precisely what I love about bikepacking. Not the slumming, necessarily, but the overcoming of the slumming. Like most adventure sports, bikepacking can be as easy or as hard as you want to make it. More often than not, I find myself just cresting the threshold between Type I and Type II fun, the difference between fun in the moment and fun in retrospect. Having bikepacked the 2,700-mile Great Divide Mountain Bike Route and shorter routes like the TransVirginia and the 250-mile RockStar route, I know full and well that on any given day of a bikepacking tour, I can experience the gamut of emotions, sometimes all within the same hour.

No Valleys, No Peaks

Even on day one, it was clear that the TransVirginia would be fraught with ups and downs. Our 8 a.m. departure from Washington D.C., was hardly early enough to escape the heat last September. By 10 a.m., temperatures had soared above 95 degrees. Humidity hung heavy in the air. The changing of the seasons was only a week away, but summer still reigned mercilessly.

The first 50 miles of the route skirted northern Virginia’s traffic via rail-trails. We made quick work of the flat miles, but not without consequence. By mile 55, we both were cooked. Head swimming, legs shaking, I was so hot I’d stopped sweating. As we neared an intersection at the 60-mile mark, Lindsey called over her shoulder.

“Are we going right or left up here?”

I looked down at my phone and zoomed in on the route. We were approaching a left hand turn onto Yellow Schoolhouse Road.

“Yellow,” I blurted. Lindsey paused, looking back at me, her eyebrows raised. “I mean, left.”

I feel good, I feel great, I feel wonderful. I forced down some electrolyte drink mix. We still had another 20 miles to go before we reached the sole campground in a sea of private land. We pedaled on, and just as we were tapping into our final energy reserves, the Bluemont General Store appeared like a mirage. A sign touting ice cream, fresh eggs, and harness bells lured us inside. Sitting on the deck with a cold lemonade and a handful of hard-boiled eggs, I felt reborn, or perhaps just rehydrated.

By day three, the heat had abated but the humidity had not. Our shirts and chamois were perpetually damp. Soaked with sweat as we were, the land around us was completely parched. Every stream and creek and spring we passed was dry, a disconcerting realization given the 8,000 feet of climbing ahead that day.

The first 3,500 feet of climbing came painfully slow, following washed-out singletrack and steep gravel Forest Service roads, but I forgot about the effort as soon as we started to descend. In five miles, we ripped down 1,400 feet in elevation to the unincorporated community of Mathias, West Virginia.

But soon, we were climbing again, this time on chunky doubletrack littered with baby-head-sized rocks. Our pace slowed from 13 mph to 10, then 8, then 5. I was down to one half-empty water bottle for the remaining 20 miles. If the dry riverbed beside us was any indication of the water to come, we were screwed.

As we topped the ridge, thunder rumbled overhead. At the first drops, we took cover beneath the scrawny limbs of a pine tree. Rain poured from the sky in a heavy curtain, but just as soon as it started, the downpour stopped.

The previously hard-packed road was now miserably muddy. We navigated around the edges of hub-deep puddles the color of tomato soup. Soft clay turned to sand turned to grass. For the next eight miles, we picked our way along overgrown doubletrack. Stinging nettle and briars stung and tore our skin. Downed branches threatened to rip the derailleurs from our bikes. I feel good, I feel great, I feel wonderful.

As we rounded a bend in the track, late-afternoon light filtered through the trees. The forest sparkled in brilliant hues of gold. Even the stinging nettle looked magical. Our spirits boosted, but our thirst still far from satiated, we cranked out the final miles, unsure if our next creek crossing would be flowing or dry. We were in luck. Out of the many feeder creeks that dump into Switzer Lake, only one remained flowing.

Spared, Again

Back in the highlands of Mount Rogers National Recreation Area, Lindsey and I run into a road closure, the second one we’ve encountered on our trip. At the first closure 130 miles ago, we’d ignored the sign, choosing to take our chances instead of rerouting and adding mileage to our already big day.

The road, we discovered, was closed for good reason. The Virginia Department of Transportation was rebuilding a bridge that crossed over a steep ravine. Were it not for the temporary catwalks—and some good-natured VDOT workers who used their crane to get our bikes from one side of the bank to the other—we would have been forced to backtrack and reroute.

It is getting dark. We are exhausted and, unsurprisingly, almost out of water. We decide to take our chances again and forge ahead. Before long, we come upon two bulldozers bookending a construction site and blockading the road. We waste an hour bushwhacking through the thick rhododendron to get around.

Finally, some three hours later, we top out on the climb and begin the final descent to our campsite at Comers Rock. Our water bottles are empty, stomachs grumbling, legs entirely worked, but we have made it. The day’s 97-mile haul sets us up perfectly to finish the TransVirginia the following day.

We collapse in a pile of bikes and gear at the first campsite we see and stumble over to the water pump. In the fading light, I can just barely make out a sign hanging on the spigot. OUT OF ORDER.

Lindsey and I don’t need to say anything. The despair is palpable. We are too tired to ride farther in search of water, but too thirsty to go without. Not even Bob’s words can help me now.

And it is here, at the bottom of the barrel, that the universe steps in with a simple act, a fortuitous meeting of time and space that, the more it happens, feels less coincidental and more like fate. After not seeing a soul for hours, we hear a voice call to us from across the otherwise empty campground. It’s the campground host, and he has water. We are spared.

Interested in riding the TransVirginia Bike Route? Check out these FAQs to get started.

When is the best time of year to ride the TransVirginia?

Mid-April through October is typically the most ideal weather window for riding the TransVirginia. Snow and freezing temperatures are known to linger in elevations above 4,000 feet in April and October, so be prepared to experience a wide range of temperatures during those months.

How long does it take to ride?

Most riders touring the route will take anywhere between nine and 15 days to complete the route, riding an average of 36 to 61 miles per day. The current fastest known time for a southbound independent time trial is 3 days, 14 hours, 58 minutes.

What is food/water availability like?

The TransVirginia passes gas stations and country stores every 50-60 miles. Riders will not have trouble finding surface water to filter; however, some springs can dry up during the heat of summer.

What bike should I ride?

This route features a variety of terrain, from smooth pavement and well-maintained gravel to chunky doubletrack and singletrack. A gravel bike with bigger tires (at the very least, 40-45mm, but 2.0” is recommended) and low gearing will make the rocky roads and steep climbs much more enjoyable.

How does the TransVirginia compare to rail-trails like the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal?

The TransVirginia is a serious step up from touring rail-trails. The route features almost 46,000 feet of climbing in 550 miles, with 60% of those miles navigating off-road terrain. However, TransVirginia route developers recently released a “Valley TransVA Alternate Route,” which reduces the overall elevation gain by 13,000 feet. This alternate can more comfortably be ridden on a gravel bike with 30-40mm tires. For more information on all things TransVirginia, visit www.transvirginia.org.