“Most of the park is wildlife habitat available for bears. But there are parts that are people habitat: campsites, picnic areas, parking lots,” explains Bill Stiver, a wildlife biologist in the Smokies who has focused on bear management for over 20 years. “If we allow bears to be comfortable around people, sooner or later they’re going to get into garbage. And when that happens, eventually you’re going to have bears climbing on picnic tables and breaking into cars.”

Bears that go searching for trash and human food are “nuisance bears.” A major part of Stiver’s job involves managing nuisance bears, both with preventative and rehabilitative measures.

Instinctively, black bears are afraid of people. “When they encounter a person, they take off running,” Stiver says. “They don’t want anything to do with people.” But if there’s food lying around after people are gone, a bear may investigate. If the problem continues, the bear will show up night after night. As long as there’s still the promise of food, says Stiver, “they’ll get bolder and bolder and show up earlier and earlier.”

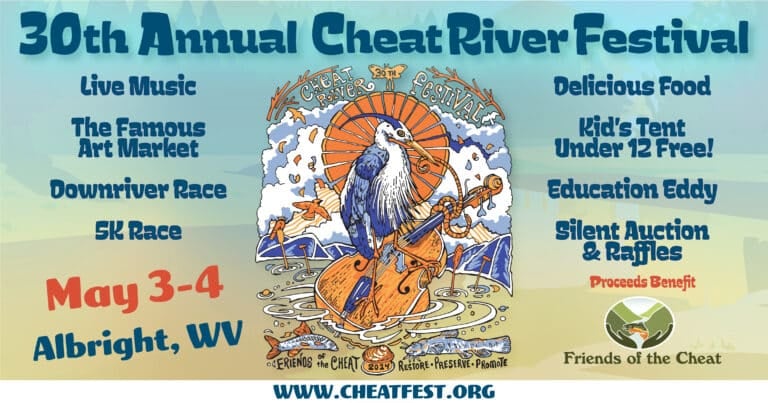

The key to preventing nuisance incidents is education, he says. The biologists and park rangers in the Smokies do their best to educate people about proper food storage and proper trash disposal. Signs are posted around campsites alerting campers and hikers that they will incur fines for violating storage rules. But the park still occasionally ends up with dumpsters overflowing with garbage and campgrounds cluttered in food and trash.

Even if we’re 90 percent successful in educating the 10 million visitors to the park, that still leaves one million people who may not be aware. And it just takes a handful of people to start a problem.”

When park officials are alerted to a nuisance bear, they set a trap to catch and tranquilize it. Their goal is to fuel the bear’s fear of people. After weighing, measuring, and then ear-tagging the bear, park biologists will re-release it into the mountains. Usually, Stiver says, this strategy is successful. When a bear keeps returning to the scene of its crime, though, the biologists must resort to removing it from the area. Since bears have acute homing instincts, that means moving the nuisance bear at least 40 air miles away, Stiver says. “We don’t like doing that. But it is an option.”

Occasionally, nuisance bears will be moved into captivity. The Maymont Foundation in Richmond, Va., is home to one of the region’s only exhibits of native bears. One of Maymont’s two male black bears is a former nuisance bear who broke into a house trailer searching for food. Incidents like these occur when bears cannot find natural sources of food, something that is becoming increasingly difficult for them as their habitats shrink.