My friends described a secret world lurking beneath the mountains, one with narrow passages leading to underground waterfalls. Caves abound right in my backyard, or rather, under my backyard. Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia have over 14,000 caves, making it the area with the highest concentration of caves in the U.S. I couldn’t wait to see for myself. But what about bats?

Often viewed as flying rodents with rabies, bats get a bad rap. Turns out bats aren’t dangerous little creatures after all – they actually save us money and keep us healthy. Bats are the primary predator of nighttime insects that ruin crops. Without bats, farmers would be forced to turn to dangerous pesticides more frequently. A 2011 study by the U.S. Geological Survey reported that bats save farmers more than $3.5 billion a year in reduced pesticide use.

Bats keep us healthy in another way. By keeping the insect population in check, bats reduce the spread of disease. Eating some 1,200 mosquitoes per hour during their feeding time, even just one bat in our backyard reduces our risk for contracting dengue fever or the West Nile virus. In recent years, a deadly fungus called White Nose Syndrome has decimated bat populations across the East. White Nose preys on bat colonies during hibernation, when a bat’s strength is already low and its immune system is suppressed. The fungus displays itself with a white smudge on the bat’s muzzle. Bats with the fungus behave oddly, like flying outdoors during cold winter months or gathering at cave mouths when they should be hibernating. As a result, bats burn off their winter fat reserves, making them much more susceptible to freezing or starvation.

Scientists estimate the fungus has already killed some 5.5 million to 7 million bats across 20 states, since the problem was first detected in 2006. If a solution isn’t found, several species of bats could become extinct within the next 20 years. The fungus flourishes in cool environments so the year-round 55 degree Fahrenheit temperature of most caves is ideal.

My decision to go caving turned on both legal and ethical considerations. I planned to go caving in Georgia, where caves remain open. Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources considered mandatory cave closures because of White Nose Syndrome, but ultimately decided against it. Many other states have imposed mandatory cave closures to human traffic, but none of them report successfully containing the fungus.

But just because I could legally go caving, didn’t mean that ethically I should. Before making my decision, I considered whether I would be spreading the fungus. Many speculate that recreational cavers exploring different caves with dirty equipment carry the spores with them. Since this was my first time venturing into a cave, my gear posed no potential for spreading the fungus. Knowing there was no chance of being a so-called “pathogen polluter” went a long way to quell my conscience.

Still, I wondered whether my very being in a cave would disturb the bats. I rationalized it this way: When I learn something firsthand, the experience becomes intertwined with how I view the world. The more time I spend in nature, the more personal and important the preservation of the mountains, rivers, forests, and, yes, especially the bats, becomes to me.

Going Deep: Caving at Pettijohn’s

Our caving destination, Pettijohn’s Cave, is a wild cave in Lafayette, Georgia. Folks refer to it as “sacrifice cave” because it’s so accessible, sparing other nearby caves from visitors. Although the six miles of known passages are well mapped, Pettijohn’s still presents the possibility to discover new routes.

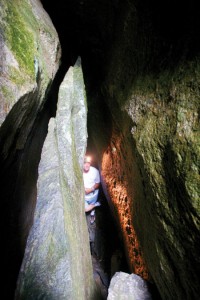

Left to my own devices, I would have walked right past the cave entrance. Our group leader led us to a rock cluster and started maneuvering his body around the boulders down a chute, which at first glance appeared to be a dead end.

I followed him through a short passage to an enormous room. The aptly named “Entrance Room” is some 500 feet long and 30 feet high. Red clay adorned every inch of the cave’s surfaces, from ribbons weaving decorative patterns on the walls to spiral projections coming out of the floor.

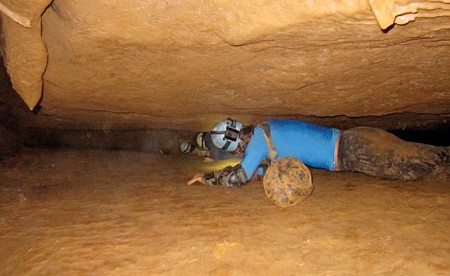

We continued to the far end of the room, where we slid, scrambled around boulders, and belly crawled through the “Pancake Squeeze” to reach a narrow chamber. Using ropes, we lowered ourselves down to an underground stream.

Water flowed under our feet as we followed it upstream toward the main waterfall. Walking upright seemed like a luxury after crouching for so long.

After scaling the waterfall, we followed a tunnel to another big room. We decided to rest, and turned off our headlamps. The moment the last headlamp clicked off, I felt as if someone had covered me with a thick wool blanket, so heavy was the darkness. It occurred to me just how amazing bats are, that they can thrive in complete darkness. Echolocation, a kind of built-in radar system, helps bats navigate at night. Bats make a twittering sound that’s so high-pitched most humans cannot hear it. When the sound bounces off objects, bat’s keen ears can actually identify the location, size, shape, and even texture of an object based on the echoes. As I grappled in the darkness for my pack, I had a whole new appreciation for bats.

After scaling the waterfall, we followed a tunnel to another big room. We decided to rest, and turned off our headlamps. The moment the last headlamp clicked off, I felt as if someone had covered me with a thick wool blanket, so heavy was the darkness. It occurred to me just how amazing bats are, that they can thrive in complete darkness. Echolocation, a kind of built-in radar system, helps bats navigate at night. Bats make a twittering sound that’s so high-pitched most humans cannot hear it. When the sound bounces off objects, bat’s keen ears can actually identify the location, size, shape, and even texture of an object based on the echoes. As I grappled in the darkness for my pack, I had a whole new appreciation for bats.

Our break ended abruptly when our leader explained that we were in an area of the cave dubbed the “Nervous Breakdown Room” because of the large number of unstable rocks known to exist there. Within a few minutes, I got into a rhythm of squeezing and twisting my way past rocks.

The last one in our group of four had just entered the chamber when I felt the rocks around me suddenly shift, making an initial booming sound followed by the sound of dozens of smaller rocks falling. When the last in our group entered the tight chamber, he leaned against an unstable rock, causing other rocks to shift and tumble down the narrow chute. His cursing mixed with the tumbling rocks, creating a sound of chaos and confusion, which echoed off the cave walls. There was now darkness above me where his headlamp had shone. When we called his name, he replied in a voice strained with fear. His left foot was pinned by a rock.

Our leader calmly leapfrogged backwards over me to reach him. While he worked to free her foot, I remained as still as possible, not wanting to set off a second rock fall. My thoughts darted. Could I move my body? Was there a path out or were we stuck? Could anyone get help quickly enough? Was I able to reach my food and water in my pack? And I thought about my baby boy, and my mind lingered on this one particular thought – what exactly was I doing in this cave when I could be at home, warm and dry holding my beautiful baby? I started to pray then, to whomever I pray to when things get really bad, and it may have been a coincidence, but just then our leader successfully freed our friend’s leg.

Now able to move, we began to ascend with slow, deliberate moves, taking great care not to shift another rock. Silence settled in as we solemnly retraced our steps back to the entrance. Our excited chatter long gone, we moved quickly to put distance between ourselves and the rock collapse. I was so focused on moving swiftly that I bumped right into my friend. He told me to turn off my headlamp, while switching his own headlamp to night vision.

Gazing up, I saw dozens of sleeping bats. A sense of child-like wonder filled me. Wrapped snuggly in their own wings and hanging by their tails, bats looked so unlike any other mammal I’d ever seen. My thoughts drifted to my own two-year old boy. I made a wish – that one day he too might stand in a cave, experiencing the same sense of awe as he cranes his neck to get his first peek of a sleeping bat. In that instant I realized just how big the stakes are for these creatures—and for us.

A short walk later we emerged from the cave, feeling off balance, like sailors stepping off a ship after a long stint at sea. I exhaled deeply, relieved to have a good scare behind me.

My next breath was a deep one, full of urgency at the task ahead. If we want future generations to be able to share this same sense of wonder, we must figure out how to prevent bats the fate of extinction. Saving the bats goes beyond preserving health and economic benefits for ourselves – saving the bats is essential to preserving our own humanity.

How to Save Our Bats

Bats need human allies for survival. Here are five ways you can help save our bats:

1. Spread the word that bats are worth saving. Write a letter to the editor or give a brief presentation at an outdoor club meeting. Not a writer? Simply like the “Save Our Bats Campaign” on Facebook and share the page with your friends.

2. Support the Wildlife Disease Emergency Act, which allocates $10.8 million in research money to stop diseases that threaten endangered species like some species of bats.

3. Preserve bats’ natural habitat, so that bats can live without too much human interference. This means limiting access and preserving the habitat inside of caves, as well as the streams, fields, and marshes bats also need to hunt insects.

4. Get your kids involved. Bat Conservation International gives kids the opportunity to adopt a bat.

5. Limit cave trips and follow decontamination protocol. Make sure to decontaminate your gear between trips underground. Both Woolite and Formula 409 kill the fungus without harming caving gear. And consider following the example of other cave stewards — set up weekend decontamination stations in the most popular caving destinations, to reduce the chance of humans spreading the fungus.