YES

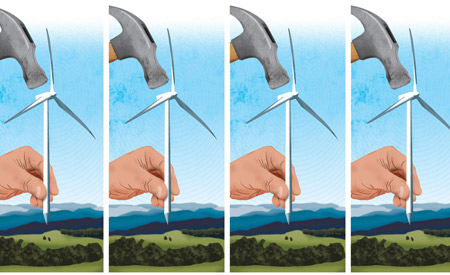

Appalachia remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, and these have a devastating impact on the land, air and water, including literally removing mountains for coal extraction. To address these concerns, we need a mix of energy efficiency and renewable energy. The smart development of wind energy in select areas of Appalachia will allow us to better tackle the challenges of meeting the ever-growing energy demand while simultaneously reducing emissions and local environmental impacts.

But why should wind farms get built in Appalachia instead of off coastal shores or on windy plains? The truth is that we need wind farms built in all these areas. A study published by the National Renewable Energy Lab in 2012 highlighted that geographic diversity of renewable energy resources helps ensure a steady supply of power. If the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining in one part of the country, it likely is elsewhere.

Once built, wind farms emit no pollution, consume no water, and burn no fuel. A study published in the journal Energy Policy found that, on a per-unit of energy basis, fossil fuel power plants are 19-times worse for birds than wind turbines. This past year, more wind energy capacity was installed than any other generation resource, beating out coal, natural gas, and nuclear power.

Even so, wind turbines should not receive a free pass to be installed anywhere. Wind farm developers typically take several years for a site assessment to determine potential impacts to habitats, birds and bats, and other environmental concerns. Developers sometimes undergo a viewshed study to evaluate how a wind farm will look from various viewpoints. Some evidence exists that wind farms may even help spur tourism. Certainly, people are fascinated by wind turbines. I’ve experienced their appeal myself; when planning a fly-fishing trip to West Virginia, my wife chose a bed and breakfast that had a wind-farm view. Had we been on the other side of a ridge, we wouldn’t have known a wind farm was nearby.

Done in the right way, wind farms will tap the wind-rich resources of Appalachia while reducing the negative impacts incurred through traditional energy generation. While the suitability of a wind farm varies from site to site, one thing is for sure: more of them should be built in Appalachia.

Simon Mahan is the renewable energy manager for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

NO

I recognize the need for alternative energy. I am aware of the harm caused by reliance on coal, and I am concerned about global warming. Appalachian wind development, however, is more of a distraction than a solution to these problems. And it threatens some of the best of the region’s wild landscape.

Ridgeline wind projects typically require extensive forest clearing and excavation for roads, turbines, powerlines, and substations. With about a mile needed for every seven turbines, even low-capacity projects result in substantial habitat loss and harm to wildlife. The environmental footprint is simply too large in relation to the benefits.

Suppose, for example, we want wind-powered electricity in the summer months when minimum wind availability coincides with maximum electricity demand. Let’s say we want to supply enough electricity to replace just one relatively small 500-megawatt power plant. This very modest objective would require about 300 miles of ridgeline turbine construction, and we would still need another readily available source of power for when there is no wind.

Let’s not give the wind industry a pass on environmental review. We should not back away from protection of golden eagles and other wildlife that use the mountain ridges, and projects should not go forward where high bat mortality is expected.

Let’s look at other options. Offshore wind development, for example, makes more sense than wind development in the Appalachian mountains—in terms of both electricity generation and environmental cost.

And let’s redirect the incentives that finance the wind industry. We could achieve much more with support for residential and urban solar development—something that will actually allow people and communities to assume responsibility for meeting their own electricity needs without harming the environment.

And finally, if we are really serious about solving our energy-related problems, we should expect our elected leaders to adopt energy policies that are based on informed analysis instead of wishful thinking.

Rick Webb is a senior scientist at the University of Virginia.