Virginia State Route 80 is paved and winding. From the old timber town of Haysi, Va., the road makes a wide birth around the Russell Fork River, rolling along the Cumberland Mountains until it reaches the Virginia-Kentucky border where it makes a hard right to parallel the river into Elkhorn City, Ky.

A scattering of houses face the road, tucked into their respective hollers. Washed-out dirt roads diverge from the pavement and disappear into the forest, leading to old logging sites and mountaintop removal mines. Locals congregate in the gravel parking lot of the Laurel Shop. There’s always a distant rumbling—in some bends of the road, it’s the river you hear, in others, the methodical churning of the Kingsport Subdivision rail line.

This is coal country.

It’s also home to one of the most overlooked recreation destinations in the Southeast—Breaks Interstate Park, one of only two interstate parks in the country. Established in 1954, commissioners from both Kentucky and Virginia oversee management of the park, which, combined with its funding, is what separates this interstate park from typical state park designations. A major tributary of the Big Sandy, the Russell Fork forms the Breaks’ westernmost border with more than 4,600 acres of rugged terrain sprawling northeasterly in elevations ranging from 920 feet at the river’s edge to 1,978 feet at the Clinchfield Overlook.

Kayakers know and love this diamond-in-the-rough. Where the upper stretches of the Russell Fork and the Pound River are relatively mild in nature (class II-III+), it’s the steep class V rapids of the Russell Fork Gorge that have garnered respect and admiration from the international paddling community since the early ‘90s.

Here, the river plunges up to 190 feet per mile, snaking through boulder gardens and enshrining paddlers in a 1,650-foot vertical canyon. The Lord of the Fork, an annual downriver race through the heart of the gorge, takes place on the last Saturday of the release season. The likes of professional paddlers such as Pat Keller, Adriene Levknecht, Dane Jackson, and Chris Gragtmans regularly compete in the Lord of the Fork, and spectators and racers alike choke the campgrounds every October.

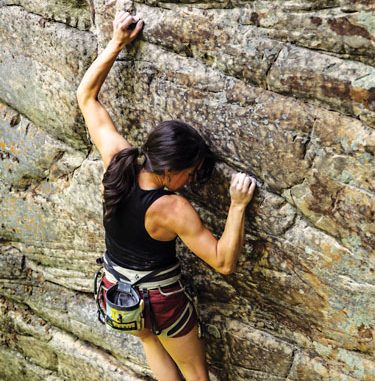

But this year, paddlers may have a little less elbow room at the Breaks, thanks to a recent sanction that allows a new means of recreating within park limits—rock climbing.

“[The park] has the potential to have 1,000 routes,” says Kylie Schmidt, 26, of Pikeville, Ky. “It’s like the new New.”

Schmidt, who grew up hiking in the Breaks with her family, played an instrumental role in opening the dialogue between climbers and the park back in 2014. A longtime area climber, Schmidt and her University of Kentucky peers mostly frequented the Red River Gorge, an internationally renowned climbing destination just over an hour’s drive from campus. One weekend in 2012, Schmidt convinced her friends to make the trip to her hometown stomping grounds. The park amazed the crew, greeting them with quiet crags, untouched routes, stunning vistas…and a visit from Breaks Superintendent Austin Bradley.

“That was my first interaction with him,” Schmidt admits, almost sheepishly.

But Bradley didn’t write them up. There was no fine for breaking the rules and hardly a slap on the wrist. That’s because Bradley knew Schmidt and her posse of college friends weren’t the first, and certainly wouldn’t be the last, climbers in the park.

“The Civil Air Patrol and some of the local college programs and rescue-and-response agencies were allowed to climb and rappel and do different things in the past,” says Bradley, “but it also wasn’t well posted that climbing wasn’t allowed, so some people just came and climbed just not knowing that, technically, it wasn’t a sanctioned activity.”

“In hindsight, I should have gotten serious about pushing for getting climbing established legitimately, but I was so new to climbing, I didn’t understand how great of a resource the Breaks was,” says Schmidt.

Two years after Schmidt’s encounter with Bradley, an article in the University of Kentucky campus newspaper announced that the Elkhorn City Heritage Council was seeking opportunities to expand outdoor tourism in the hopes of revitalizing the area’s dwindling economy. For Schmidt, it was the moment the lightbulb finally began to flicker. Could climbing help save coal country?

“We’ve seen that happen in the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, we’ve seen that in the Obed in Tennessee, and the New River Gorge in West Virginia, and I think we’ll see it at the Breaks as well in coming years,” says Zachary Lesch-Huie, Southeast Regional Director for the Access Fund. “The Breaks is a great example of how opening climbing access isn’t just about a win for climbers—it’s a benefit to the communities as well.”

After learning the park was in the midst of a 30-year master planning process, Schmidt became determined to make climbing a part of the park’s future. She enlisted the help of Lesch-Huie and Brad Mathisen with the Southwest Virginia Climbers Coalition. The team didn’t need to look far for proof of climbing’s positive impact.

Just this year, Eastern Kentucky University released a study showing that climbers alone spend an estimated $3.6 million per year in the regional economy surrounding the Red River Gorge, $2.7 million of which goes directly to local small businesses and supports 39 full-time jobs in an area with high poverty rates.

“The coalfield counties of southwest Virginia and eastern Kentucky are in a kinda enormous economic transition right now,” says Bradley. “That was one of my goals in pursuing opening climbing in this area. I think we have a really significant resource and I think people will come to utilize it and that really fits into the broader scheme of what’s going on in this area in trying to, instead of extracting our resources, utilize what we have left to attract tourism.”

“I could see Elkhorn City becoming like a mini Asheville,” says Schmidt. “It has phenomenal opportunities for whitewater rafting, fly fishing, mountain biking, and climbing.”

With five miles of quality sandstone clifflines that rival the rock found in the New River Gorge and Obed Wild and Scenic River, the park is long overdue in recognizing the opportunities. What’s more, the infrastructure and amenities are, largely, already in place. The roads are all paved in the Breaks. There’s a visitor’s center, a lodge, a restaurant, and a campground. The park has plenty of trail markings, parking lots, and maps. The 25-mile multiuse trail system in the Breaks practically takes climbers to the base of the climbing areas with minimal bushwhacking involved.

Since the sanction went public on May 1, 2016, the Breaks’ five open climbing areas already have 21 sport routes and 37 traditional routes established. Despite concerns about impacts to the park’s resident peregrine falcon population, which has successfully recovered since the DDT scare of the ‘70s, Bradley is confident that climbers will be respectful of the sensitive natural and historical aspects of the park. He is hopeful that more areas at the Breaks, like the iconic Towers formation, will be open to climbing in the coming years.

Climbing at the Breaks is on a permit basis only, though the permit is free and easy to acquire at the visitor’s center. Rules and regulations on bolting and route development in the park are available at mountainproject.com.

Untapped Climbing

Tired of your busy backyard crag? Craving a quiet wall sans gym rats? Look no further. We’ve consulted a handful of the region’s top rock aficionados to bring you a list of off-the-beaten-path climbing destinations. Sure, you might end up off-route, totally lost, and benighted. But that’s when the adventure really begins.

Guest River Gorge

Virginia

Situated in the westernmost corner of southern Virginia, the Guest River Gorge is like an undeveloped New River Gorge. Sandstone clifflines jut upwards of 100 feet tall and are easily accessible by way of the Guest River Trail (and a few minutes of bushwhacking). If rope climbing’s not your thing, the river bank is littered with quality boulders that have more potential than there are climbers to project them.

NEAREST CITY: Norton, Va.

Approach: Easy hiking on a reclaimed railroad bed

Style: Sport, bouldering, some trad

Recommended Route: Power and the Glory, 5.10b

Beta: mountainproject.com

Season: Spring, fall, winter

Word from the Wise: “Access here is allowed, but tenuous. Land management here is okay with climbing but not with continued development of new climbs.” —per Access Fund

Old Rag Mountain

Virginia

A classic among hikers, Virginia’s Old Rag Mountain also offers stellar splitter, corner, and face climbing for those willing to go the extra mile. It’s like a mini Yosemite, packed into a single pitch.

NEAREST CITY: Sperryville, Va.

Approach: The car-to-summit distance is 2.8 miles with a vertical gain of about 1,760 feet. Typical hiking time to the summit is 1 to 1.25 hours.

Style: Trad and some sport

Recommended Route: Strawberry Fields, 5.9+

Beta: Rock Climbing: Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (A Falcon Guide by Eric Horst)

SEASON: Fall, late winter, early spring

Word from the Wise: “Old Rag is a remote and fairly serious climbing area with a long, rugged approach. Bring a headlamp and twice the water you think you’ll need!”

—Eric Horst, Guidebook Author

Bozoo

West Virginia

If you’re looking for a place to take beginners without the pressures of a crowded crag, this is the spot. Top rope setup is easy to come by at Bozoo and with endless moderate bouldering, riverside camping, and south facing cliff bands, this overlooked climbing area is enjoyable practically any time of the year.

NEAREST CITY: Bozoo, Va.

Approach: Short five-minute hike uphill to the first climbing zone, Iceberg Area

Style: Trad, mixed, and some sport

Recommended Route: Homer, 5.11b

Beta: Rock Climbing: Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (A Falcon Guide by Eric Horst)

Season: Year-round climbing is possible, although spring and fall are best.

Word from the Wise: “The crags are located on the edge of Bluestone Lake State Park, and portions of the rock may lie on private property. At present there are no restrictions.”

—Eric Horst, Guidebook Author

Laurel Knob

North Carolina

This big, bad, 1,200-foot granite dome is arguably the tallest exposed cliff face in the East.

NEAREST CITY: Cashiers, N.C.

Approach: Start early. It’s about a two-hour hike in featuring a 600-foot descent down countless switchbacks.

Style: Trad, multi-pitch

Recommended Route: Have and Not Lead to Fathom Direct, 5.10+ R, eight pitches

Beta: mountainproject.com

Season: Spring, late summer, fall

Word from the Wise: “This is the best slab rock I’ve climbed anywhere in the world, from Yosemite to Chamonix. It’s slab climbing, but it climbs more like a technical face with moves well above pieces of gear with big time fall potential.” —Karsten Delap, Professional Rock Climbing Guide, Fox Mountain Guides

Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area

Tennessee

Big South Fork is a 125,000-acre frontier with sandstone cliffs here reaching heights in excess of 200 feet. Many areas here also feature large tiered roofs, which means you can climb even in the midst of a Southeast maelstrom.

NEAREST CITY: Oneida, Tenn.

Approach: Bushwhacking, river crossings, unmarked trails, you name the genre of adversity, and Big South Fork’s got it.

Style: Mostly trad, some sport, some multi-pitch

Recommended Route: Vertigo, 5.10 A2

Beta: mountainproject.com

Season: Spring, fall, winter

Word from the Wise: “Many of the harder routes at developed areas have seen only a handful of ascents, often fewer than that, and as a result, loose rock can be a hazard especially on ledges. It would be a complete crapshoot to climb at BSF without a helmet. The biggest hazard to the BSF explorer is venomous snakes—the sheer number of rattlesnakes rivals the number of unclimbed routes.”

—Scott Perkins, Professional Rock Climbing Guide, Alpine Leadership

East Slate Rock

North Carolina

This 300-foot granite face is situated in Pisgah National Forest, and as of four years ago, it was vertical terra incognito.

NEAREST CITY: Mills River, N.C.

Approach: It’s a 40-minute hike in from the easternmost Pilot Cove/Slate Rock Loop trailhead.

Style: Trad, ice in winter

Recommended Route: Slate Night Booty, 5.9

Beta: Rumbling Bald Rock Climbs (grounduppublishing.com) outlines the majority of East Slate’s routes.

Season: Spring, fall, winter (for ice)

Word from the Wise: “East Slate contains some of the best face climbing and edging around, but you’ll find cracks and corners as well. Several routes are an even mix of Rumbling Bald-style edges and flakes, mixed with water grooves reminiscent of Laurel Knob. It’s a diverse mini crag that’s way off the beaten track.” —Mike Reardon, Guidebook Author and Owner of Ground Up Publishing

Laurel-Snow State Natural Area

Tennessee

The 2,000-acre Laurel-Snow has waterfalls, shaded coves, cool mountain springs, and stunning views. It’s popular for its bouldering as well as its killer sport and trad climbing.

NEAREST CITY: Dayton, Tenn.

Approach: Hike for an hour past the bouldering area on relatively flat ground until you reach the ridgeline. Follow signs for Laurel-Snow, which will take you uphill and past more giant boulders and through numerous switchbacks. It’s relatively well-marked and obvious.

Style: Sport, trad

Recommended Route: Darwinism, 5.10d

Beta: Very little – mountainproject.com

Season: Spring, summer, fall

Word from the Wise: “People don’t really go there, but it’s really beautiful and secluded with tons of waterfalls. Its sister area, which is across the valley, is called Buzzard Point. It’s received less traffic over the years because of access issues, but it’s still an open crag and it’s huge. People just don’t go there because the hike has become really long to get to it.” —Andrew Kornylak, Adventure Photographer and Videographer

Little River Canyon National Preserve

Alabama

It’s big, it’s wild, and as any visitor to this 14,000-acre ribbon of protected land will quickly discover, it’s steep. Civil War deserters and outlaws often sought shelter here, finding quiet pockets

within the canyon’s overhanging walls that were hard to reach.

NEAREST CITY: Fort Payne, Ala.

Approach: The access roads sit above the cliffs, which means you’ll need to scramble or rappel your way to the base of the wall before beginning your climb.

Style: Sport

Recommended Route: Anything on Lizard Wall. Its slightly overhanging routes stay dry when everything else is wet.

Beta: Dixie Cragger’s Atlas: Climber’s Guide to Alabama and Georgia

Season: Any but summer

Word from the Wise: “The majority of the climbs there are 5.11 or harder. Friends of mine have broken arms and legs on those approaches. It’s the kind of approach where you don’t want to bring your dog or small kid.” —Andrew Kornylak, Adventure photographer and videographer

Tallulah Gorge State Park

Georgia

Quartzite, exposure, and scenery abound in this southeastern gem. With the Tallulah River running through it, and camping and hiking available in the park, a trip here can easily span a week without ever scratching the surface of all the gorge has to offer. The park issues a maximum of 20 climbing permits per day, but this limit is hardly ever maxed.

NEAREST CITY: Lakemont, Ga., or Long Creek, S.C.

Approach: Short scramble or 4th class downclimb

Style: Trad, multi-pitch, some mixed aid

Recommended Route: Punk Wave, 5.10a, three pitches

Beta: mountainproject.com

Season: Late fall, early spring

Word from the Wise: Go during the week. The park closes access to climbing when there are recreational releases on the Tallulah.