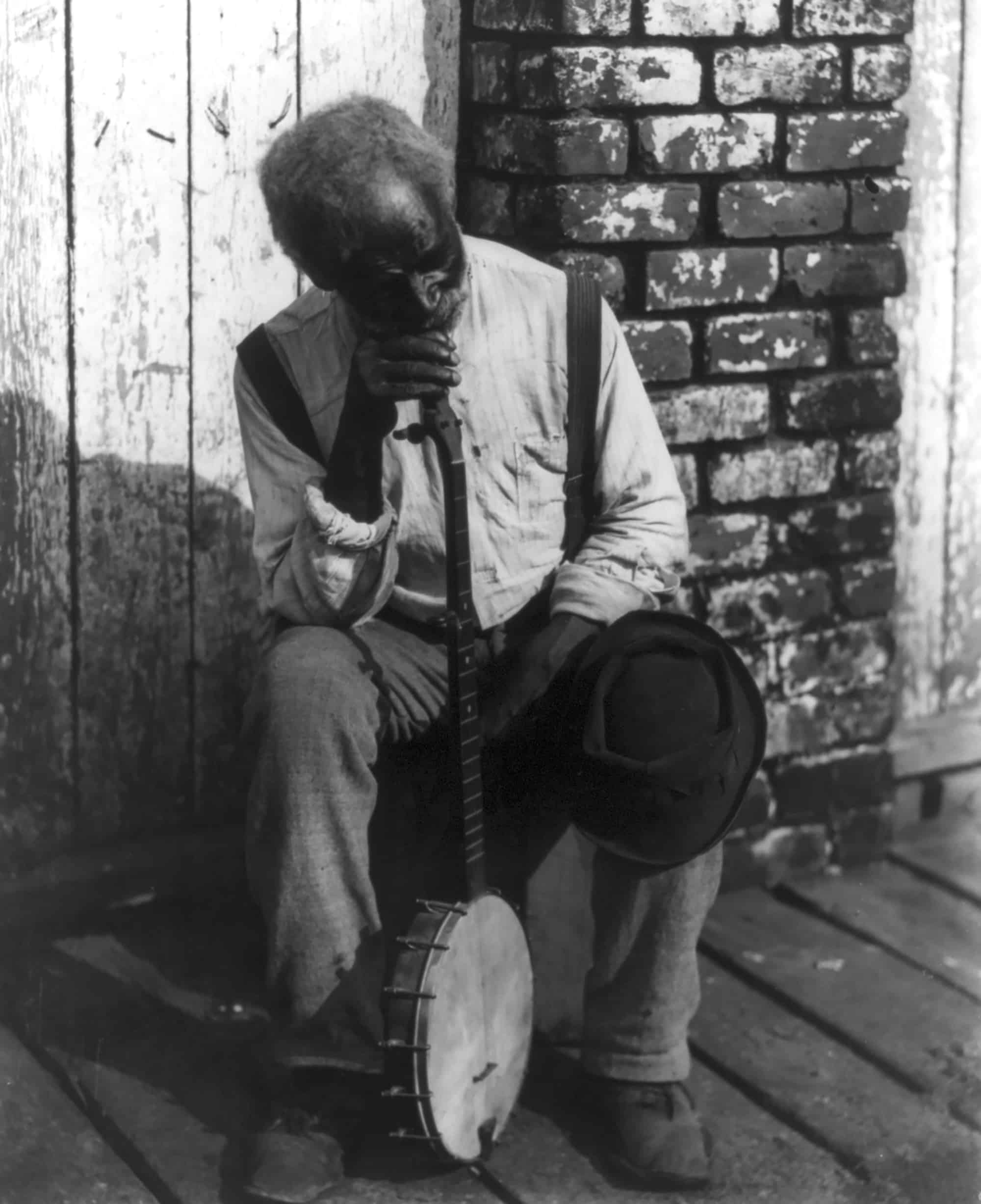

Cover photo: The banjo remained a distinctly Black instrument until the 1830s. Photo courtesy of the American Banjo Museum.

Riff in Time

When most people think of the banjo, they imagine a bearded, salt-of-the-earth man picking away in some lonesome holler. For good measure, their imagination may even embellish the scene with baying hounds, white lightning, and a mountain drawl thicker than honey.

But here’s the thing: While the banjo may be an icon of Southern Appalachia today, it hasn’t always been. That’s according to Parrish Ellis, a music instructor at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, N.C.

“The modern banjo is derived from an old African musical instrument,” says Ellis. More specifically, the banjo dates back to the akonting: a three-stringed folk lute played by the Jola people of West Africa.

With a long, exaggerated neck and a body made from a calabash gourd, the akonting is a far cry from Béla Fleck’s pre-war Gibson or Steve Martin’s Deering Clawgrass. And that’s because the akonting never made it across the Atlantic, at least in its physical form.

As Ellis explains, when Africans were forcibly brought to the Caribbean islands in the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors stripped them of their possessions—lutes included. But their native culture still accompanied them, “stowed away in souls and minds.”

In the 17th century, slaves began tapping into their “collective memory” to recreate the traditional instrument using gourds, wood, and animal hides. The result looked similar to the akonting, except with a few European touches like a flat fingerboard and tuning pegs. Despite these white influences, the banjo—also referred to as the bangie, banza, bonjaw, and banjer—remained a distinctly Black instrument until minstrelsy became popular in the 1830s.

Egregiously racist, minstrelsy was a type of theater in which white actors wearing blackface makeup caricatured Black people as buffoonish and simpleminded, and live banjo was part of these performances.

Through this cultural appropriation, white musicians became interested in the banjo. As noted by a newspaper from the time, “All the maidens and a good many of the women also strum the instrument, banjo classes abound on every side, and banjo recitals are among the newest diversions of fashion.”

Even Mark Twain was enamored with the instrument.

“The piano may do for love-sick girls who lace themselves to skeletons, and lunch on chalk, pickles, and slate pencils,” Twain stated. “But give me the banjo. When you want genuine music…just smash your piano and invoke the glory-beaming banjo.”

The glory-beaming banjo especially struck a chord in Appalachia, where it was picked up and reinvented by music legends like Earl Scruggs, who played using an unconventional three-finger style that helped spawn bluegrass. There was also Uncle Dave Macon and Snuffy Jenkins who, in the 1930s and 1940s, “made records playing banjos using their fingers to up-pick the strings instead of knocking down in a clawhammer motion,” says Ellis.

By the 1950s, the instrument’s twangy sound became a sort of anthem for mountain people—particularly white mountain people. And that was no accident, says Ben Krakauer, Ellis’ colleague at Warren Wilson.

“When the record industry first recorded music by Black musicians and rural whites in the 1920s, they chose to segregate styles of music by race,” explains Krakauer, a skilled banjo player highly regarded for his work as a solo act and in the band Old School Freight Train. Blues, jazz, and gospel music by Black performers was marketed as “race records” while banjo and fiddle music by white musicians was relegated to the “hillbilly” genre.

This, says Krakauer, created a “cultural narrative about what musical forms are played by or supposedly enjoyed by which social groups.”

In the coming decades, the perception of the banjo as an exclusively white instrument would be perpetuated in films and television shows like “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “Hee Haw,” and “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” The 1972 thriller “Deliverance” would also push the stereotype, depicting banjo players as backwoods whites with a needless thirst for violence.

But reality tells a different story—one in which Black banjoists like Dink Roberts, Rufus Kasey, Elizabeth Cotten, and Lewis Hairston were all making influential music with the instrument throughout the 20th century. These musicians were simply “less visible” than their white counterparts, says Krakauer. “But there have always been Black banjo players,” he confirms.

And there always will be, says Ellis. As he points out, Black banjoists like Dom Flemons, previously of the Durham-based string band Carolina Chocolate Drops, are making a lasting impression. “Young, Black musicians are picking up and mastering the instrument and bringing it full circle back into African-American culture,” says Ellis. “For me, that’s the most exciting development of the 21st century.”

A New, Old Sound

If you think you don’t like the snappy twang of the banjo, give these three contemporary pickers a listen.

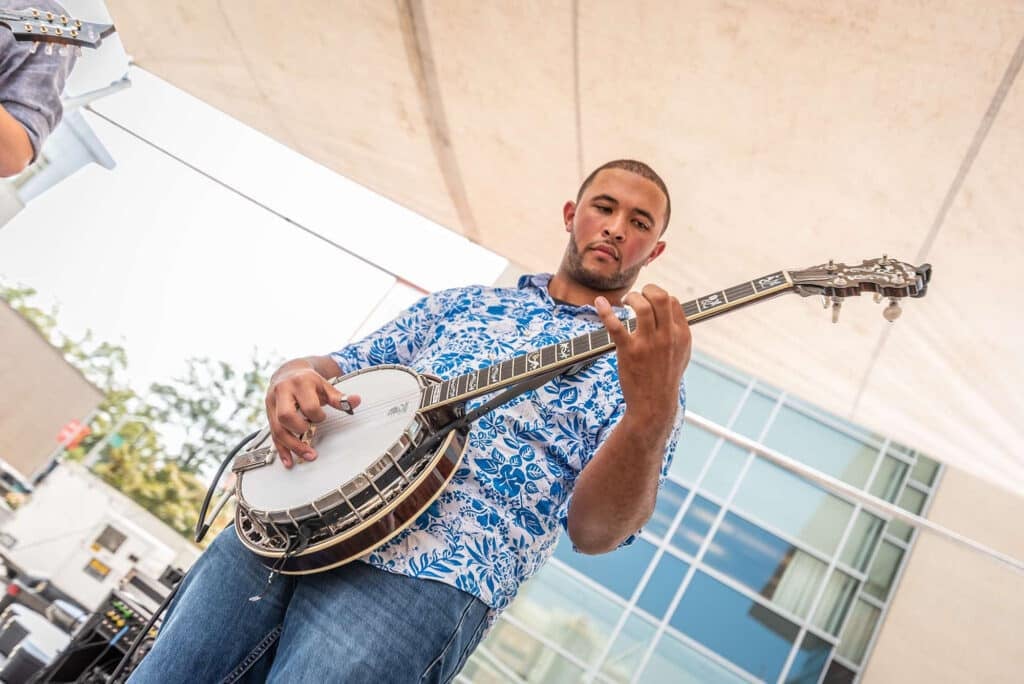

Tray Wellington

North Carolina native Tray Wellington didn’t wait long to burst onto the music scene. By the time he finished high school, Wellington was touring with the Watauga County bluegrass group Cane Mill Road. Since then, he has earned himself an International Bluegrass Music Association Momentum Instrumentalist of the Year award and produced a full-length album. Released last year, “Black Banjo” defies genres by taking inspiration from jazz musicians like John Coltrane, blues icons like Muddy Waters, and modern hip-hop artists like Childish Gambino. traywellington.com.

Kathryn O’Shea

In 2018, singer-songwriter Kathryn O’Shea moved from Atlanta to her native Asheville with hopes of “tending her roots.” Since then, she’s been laying down cathartic tracks featuring her otherworldly voice and the electric banjo. The resulting sound is something of a country-fried Florence Welch. You can’t help but be transported to a snowy mountain road, a freshly-cut lawn, or wherever else O’Shea chooses to wander. kathrynoshea.com.

Amythyst Kiah

Hailing from eastern Tennessee, singer-songwriter, guitarist, and banjoist Amythyst Kiah offers a gritty, indie folk-infused style she describes as “Southern Gothic.” Fittingly, songs released on her 2022 EP “Pensive Pop” and her 2021 album “Wary + Strange” explore melancholic topics like suicide, racism, and alcohol abuse. Listening is a weighty experience, sure. But Kiah is sure to lighten the mood with velvety smooth vocals, twangy riffs, and toe-tapping beats. amythystkiah.com.