Meet 10 inspiring outdoor parents and young adventurers exploring our mountains.

In 1993, Cindy Ross of New Ringgold, Pennsylvania, an accomplished thru-hiker with the Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trail already under her belt, set out to hike the Continental Divide Trail with her husband, a pair of goofy llamas, and two toddlers.

You read that right. Two toddlers.

“I was on a panel at a gathering of the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association, and I was pregnant,” explains Ross. “I asked 600 people in the audience, ‘How do we keep doing what we love most once we have kids? How about some advice?’ Everyone out there either had gray hair and didn’t start backpacking until their kids left or they didn’t have kids because they decided they loved backpacking so much they weren’t having any. I thought, ‘Well, that’s a big loss. That’s not happening here.’”

Ross and her husband were determined to continue long-distance hiking, even if they had to blaze their own trail. “We realized we were on our own. We had to figure it out.”

They began backpacking with their first child, Sierra, when she was three months old. But when their second child, a son named Bryce, was still an infant they tried to day hike up a ridge in the White Mountains. “We spent the whole day climbing with a kid on our backs. We got halfway up and it had been eight hours. We had to turn around. We said, ‘We can’t do this with two kids.’”

Later, at a party, they complained about their failed attempt to friends. As fate would have it, a man at the party overheard their complaints. He happened to train llamas and knew about an organization called the Rocky Mountain Llama Association in Colorado. The group was trying to promote llama packing as a means of long-distance hiking. “He said, I bet they would sponsor you and you could come out and do the Colorado Trail,” Cindy recounts. “And that’s what happened.”

Two days into their 500-mile hike on the Colorado Trail, Cindy and her family were hooked. When their walk was complete, they bought their own llamas, loaded them into a trailer, and brought them home to Pennsylvania. By then, the plan to hike from Canada to Mexico with toddlers was already taking shape in Cindy’s head.

It’s a sunny Saturday in late January and I am not attempting a 3,100-mile trek with my toddler. I am simply trying to climb to the top of Looking Glass Rock on the first warm day this part of western North Carolina has seen in some time. An hour ago my two-year-old, an accomplished little hiker in her own right, demanded to be freed from the baby backpack and began clambering up the trail at a glacial pace. My husband hangs back, helping her up as she trips over tree roots and slides around on the ice. I walk ahead, then stop and wait for my family to catch up. Walk ahead, then stop and wait. In this way we inchworm up the mountain.

It takes us two hours to walk the three miles to the summit—a pace that would have embarrassed me in my pre-parenthood days. Back then, my husband and I had zipped around some of the best footpaths in the world—the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal, the “W” in Chile, and the Camino de Santiago in Spain. Even in the midst of our adventures we’d contemplated children, but worried that becoming parents would prevent us from doing the outdoor activities we loved. At the time, I’d searched high and low for examples of parents who had managed to meld their love of the outdoors and their desire for a family into one. They were out there, but I had to find them.

Adventure Parents

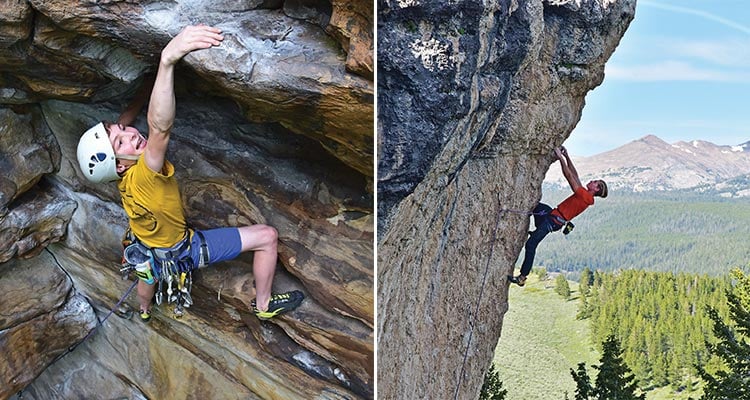

“We realized that when we had a child things were going to change,” says Dan Caston, an Assistant Professor of Recreation Leadership at Ferrum College in Virginia. “And they did change quite a bit in those first couple of years.” Before their daughter Mallory was born, Dan and his wife, Shari, climbed every weekend. “We lived out of the back of the van or out of a tent,” says Shari. “We were destination climbers playing somewhere on a rock or on the water or a trail.”

“It was difficult to get out with a baby,” remembers Dan. “But we still made it work.” Before kids, Shari and Dan favored multi-pitch climbs at Seneca Rocks. When Mallory came along they began climbing in the New River Gorge because it was single pitch and they could haul their stuff in. “There were many days that I carried in all the climbing gear and the pack ‘n play so that Mallory had a place to be while we climbed.”

Mallory was three when she did her first multi-pitch climb at Seneca Rocks. Today, at age 13, she participates on a competitive climbing team in Roanoke.

Eric Horst knows a thing or two about raising kids that climb. In addition to his day job as an adjunct professor of meteorology at Millersville University in Pennsylvania, he’s also a world-class climber, training expert, and coach. “Out at the cliffs I run into a lot of people that haven’t started a family yet but are considering it. It’s important to think about how parenting will change the way you climb.”

“If you have a kid and you go on climbing trips, it has to be different,” says Horst. “I’ve seen parents who are elite climbers who bring their kids to the cliff and just ignore them. To me, if you’re bringing your kids to the crag, you ought to be getting them involved in some way.”

By age 8, Horst’s own sons were lead climbing. By age 11 they were some of the youngest kids in the world to climb 5.14 (a grade reached by only the top 1% of climbers.) “They’ve gotten a lot of notoriety on an international scale and I didn’t set out to do that. They’re just part-time climbers. I’m not trying to get them in the Olympics or anything. I’m trying to expose them to a diverse childhood.”

Chris Hull of Richmond, Va., began kayaking in 1981. He took to the sport immediately and before long he was whitewater racing. Chris got married and eventually had four kids. When they were small, he would go out on flat water and paddle around while his kids napped in his lap. As they grew, Chris learned to let his kids explore the outdoors at their own pace. “They want to wander around and find some frogs in the creek, that’s okay. Exploring is what’s important.”

Chris taught all of his kids to paddle but his youngest son, Isaac, adopted the sport as his own. “Isaac has the disease,” says Chris with a laugh. “He really enjoys it.”

Pre-kids, Leslie Grotenhuis, owner of Kick It Events in Asheville, North Carolina, and her husband, Tim, the Executive Director of the Mountain Sports Festival, were an active outdoor couple—running, hiking, skiing and camping. Their first child, Wyatt, didn’t slow them down. “One kid was not a big deal for us,” says Leslie. “We felt like, if you can wear a kid, you can do anything.”

But as their family grew to four kids, including a set of twins, it got “exponentially harder,” says Leslie. “When you have four little ones, you can’t carry everybody. We had to hike kid-friendly trails so that the little ones could walk.”

Yet even with four kids under the age of five, the Grotenhuis clan found ways to get outside. “I remember standing in the bike store before the twins were born and discussing with the salesman how to get four children on a bike,” says Leslie. “The twins went in infant slings. They were 6.5 pounds and on the back of a bike.”

As I talked to adventurous parents for this story, two recurring themes kept emerging. The first is that, yes, adventuring with kids can be hard, especially when they’re very young. The focus of the adventure must morph from one that revolves around the parent to one that is centered on the child. As Horst explains, “those days of climbing were built around the kids. We did what was appropriate for them.” From my limited experience, that’s just the name of the game when it comes to parenting.

But the stronger and more prevalent theme was the joy that comes from sharing outdoor experiences with your kids and watching them fall in love with the wilderness. It’s a special blend of love and pride to watch your child forge their own path forward while encompassing the same values of stewardship and adventure that you hold dear. Even if your own adventures have been dialed back a notch in order to get there.

Bettina Freese explains this concept well. Freese is a fixture of the mountain biking community in western North Carolina where she lives. In addition to biking, she’s also a runner and general outdoor enthusiast. Last summer, she took her sons hiking in Glacier National Park. “I didn’t get to go backpacking or do some 15-mile trek, but we had a blast on a little 5-mile trail that was full of glacial pools,” she says. “Adventuring with kids is just fulfilling in an entirely different way.”

Adventures gone wrong

That’s not to say that the challenge of outdoor pursuits with kids doesn’t sometimes take a turn for the worse. As most parents know, kids are hard, even in a controlled environment. When we add in the unpredictable element of nature, things can sometimes go haywire.

One summer, while climbing at Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, Eric Horst and his family got caught in a thunderstorm. “We were just short of the top when the storm came in. That made us a lightning threat,” says Horst. “We were able to scramble across the ledge and get into a protected position where we could wait out the storm and let it blow over. But for me it was very stressful. The last thing I want to do is get my kids hurt.”

For all of the time that Cindy Ross spent hiking with her kids, she can only recall one instance where she sensed trouble. “We got stuck in a windstorm on a mountain ridge. It was so windy the saddles blew off the llamas,” she remembers. “We had to crawl on our hands and knees. It was scary because we didn’t know what to do, but we figured it out.” Ross then adds, almost as an afterthought, “We’ve also walked up to grizzly bears when we were picking blueberries.”

The moment when your child comes face-to-face with a free-range carnivore would be seared into most parents’ minds forever. But for Ross, it’s just one moment in a long string of moments raising her kids outdoors. It makes me think that maybe the true lesson in all of this is to follow our hearts into the outdoors, confident that sharing what we love with our kids is the right thing to do, even if it does come with a little risk.

Adventure Kids

The thing about kids is that they grow up—fast. Today, most of the children whose parents I spoke to for this story are now teenagers or young adults.

“A lot of kids drift totally away from their parents at this age,” says Eric Horst. “But the kids still love climbing and traveling, so I can hang out with my teenagers and stay close and connected to them. It’s something I imagine that a lot of parents don’t have with their 17-year-old son.”

The kids, it seems, also understand the advantages of their adventurous childhood. “My parents taught me how to rock climb and mountain bike and hike,” says Mallory Caston, Dan and Shari’s daughter. “They taught me how to be brave.”

Isaac Hull, Chris Hull’s son, told me that kids who grow up in the outdoors will be more comfortable there. Later in life, he said, they’ll gravitate toward the natural world.

And Chilton Curwen, a fifteen-year-old in Asheville, North Carolina and an impressive cross-country runner, said, “I love being in nature. Other sports are so fast, but with running you have time to think and look around and enjoy being outside.”

For Chilton, the benefits of cross-country running are vast. When I ask him what kids learn by participating in sports, his answer is surprisingly mature for a 15-year-old. When you’re running in the woods, he says, “you get a chance to see what the world was like before humans. It helps you connect with the world and appreciate it.” He went on to say that kids who spend time outdoors “won’t want to ruin nature. They’ll want to protect it because they’ll have an appreciation for it.”

Eric Horst’s 15-year-old son, Jonathan, expresses a similar sentiment when he speaks of climbing. “With other sports you’re on a developed field and you’re around a bunch of other developed things. In climbing, you’re outside; you’re in the environment. You’re kind of doing your own thing and can take in everything around you. It makes each climb you do more elegant.”

It’s been over twenty years since Cindy Ross finished hiking the Continental Divide Trail with her kids. The llamas are long gone, buried in a pet cemetery behind her log cabin. Her kids are grown and on their own. Sierra is a Fulbright Scholar in the Indian Himalayas. Bryce is an illustrator in Philadelphia. In her new book, The World is Our Classroom: How One Family Used Nature and Travel to Shape an Extraordinary Education, Ross’ kids reflect on their childhood outdoors. Sierra writes that, “What I learned from my childhood was how to actively care for my communities. I see myself as part of something bigger.”

“It’s not about what kids remember, but who they become.”

But Bryce’s reflection on growing up outdoors is particularly moving. “When you’re on a mountain ridge trying to outrun a lightning storm, the world becomes a lot bigger than you,” he writes. “You realize what you can control and what you can’t.”

Speaking of his time on the Continental Divide Trail, Bryce says, “Every so often people ask me, “Do you remember anything from it?” I reflexively answer yes, but in my mind the word memory is loosely defined. I like to think I remember seeing the world from my dad’s backpack. But for the most part I don’t recall distinct moments so much as sensory impressions, like the thrill of walking a ridgeline or the immense silence of waking up in a river valley.”

As for my own attempts at adventuring with a kid, last summer my husband and I took our then one-year-old on a canoe-packing trip in Minnesota’s Boundary Waters. I worried that we were finally pushing it too far, that the wobbly canoe and the unpredictable weather might be too much for our daughter. “Maybe we should save these kinds of trips for when she’s older,” I told a friend. But my friend encouraged me to go. “It’s not about what kids remember,” she told me, “but who they become.”

From the sound of it, these kids raised outdoors are becoming adults their parents can be proud of.