From the hills of Tennessee to the riverbanks of Virginia, the outdoor industry is fighting to regain its footing after Hurricane Helene.

On Friday, September 27, 2024, Hurricane Helene thundered into Southern Appalachia, unleashing fierce winds, catastrophic flooding, and deadly landslides.

In the months that followed, communities were left to reckon with staggering loss. The outdoor economy—a cornerstone of Southern Appalachia’s culture and livelihood—was among the hardest hit. With trails and river access points shuttered, rafters, hikers, cyclists, and climbers were left adrift.

But outdoor folk are nothing if not resilient and have blazed a path forward in Helene’s wake. Here are some of their stories.

Keeping the Spirit of Trail Town USA Alive

Damascus, Virginia

When reports of rising water started pouring in from Damascus, Va., Olivia Bailey—community liaison officer for the Virginia Office of the Attorney General—drove straight to the town’s command center. By the time she arrived, Laurel Creek had surged to 18 feet before washing away the gauge, and helicopters were pulling residents from homes in Taylors Valley.

“People were stranded. Communications were down. It was tense,” Bailey recalls.

Thankfully, there was no loss of life in Washington County. But the storm wiped out 17 miles of the Virginia Creeper Trail between Whitetop Station and Damascus and closed more than 400 miles of the Appalachian Trail between Georgia and Virginia. For Damascus—known nationwide as Trail Town USA—it was a staggering blow, hitting just as the fall tourism season was set to begin.

In response, volunteers launched Trails to Recovery, a nonprofit dedicated to long-term disaster response and trail restoration. Working with Damascus, nearby Abingdon, and other partners, the group quickly reopened the lower half of the Creeper and pushed through an ordinance allowing e-bikes, making the route more accessible to a wider range of visitors.

“The outdoor recreation economy is absolutely crucial to the viability of Damascus,” says Bailey, who now serves as a spokesperson for Trails to Recovery. “We knew we had to get the trail in a position that could sustain visitors.”

At the same time, local leaders pressed ahead with the Appalachian Trail Days Festival, the annual spring gathering of A.T. thru-hikers and alumni. Julie Kroll, the town’s recreation program director, says the decision “was a huge boost to morale for residents and visitors alike.”

Trail Days wasn’t the only draw. To diversify tourism, Damascus also rolled out Trout Days, a trout fishing tournament, and the DAM200, a self-guided dual sport motorcycle ride. Together, these events sent a clear message: Trail Town USA is very much open for business.

“We have lost several businesses but have gained a few new ones. Property values and home sales have rebounded. The talk of the reconstruction of the trail is keeping hope alive,” says Michael Wright, owner of Adventure Damascus Bicycles and Sundog Outfitter. “The future is looking up.”

Finding What Was Lost on the French Broad

Asheville, North Carolina

Debby Thomas didn’t go home for 18 nights after Hurricane Helene. Cut off by floodwaters, she and her husband, Trent, hunkered down in Black Dome Mountain Sports, the Asheville outdoor retailer they have owned for more than three decades.

“Since we were here 24/7, we were able to help those who needed fuel, stoves, water filtration systems, sun showers, and backpacking food,” Thomas says. “Black Dome ended up becoming a small gathering site for folks—friends and strangers—to gather for supplies and news.”

Though business slumped in the months after the storm, Thomas says the store survived thanks to the loyalty of Asheville’s outdoor community. “We’ve been here 41 years,” she says, “and the support of our local customers has meant everything.”

Sadly, other outdoor companies—especially those along the French Broad River—never regained a foothold. To keep displaced guides and gear shop employees employed, the environmental nonprofit MountainTrue launched one of the largest debris-removal efforts in western North Carolina’s history, using $10 million in state funding to staff cleanup crews.

“The rivers are economic engines for this region,” says Jon Stamper, who manages the program. “If we don’t restore access points, we risk losing the very thing that draws people here.”

Since spring, MountainTrue’s crews have combed the rivers by hand, pulling out everything from twisted metal to PVC pipes. They’ve also unearthed more personal items—from a coffee mug to a baby’s photo album—and, when possible, returned them to their owners.

“I’m just really proud and honored to be able to help western North Carolina,” says Mandy Wallace, who leads the nonprofit’s “Found Items” program. “This work is about more than cleanup—it’s about giving people back a piece of what they lost.”

But the story of Helene isn’t all about loss; there has also been knowledge gained. At RiverLink, another local nonprofit, leaders point to Karen Cragnolin Park as proof that flood-resilient design works. Despite being submerged under more than 20 feet of raging water, the five-acre riverside park emerged with almost no damage thanks to its wide riparian buffer and native meadow plantings.

“We believe we should look at our river parks and consider ‘less is more,’” says Lisa Raleigh, RiverLink’s executive director. “Any infrastructure should ‘go with the flow’—designed to be flooded and to withstand high-velocity waters.”

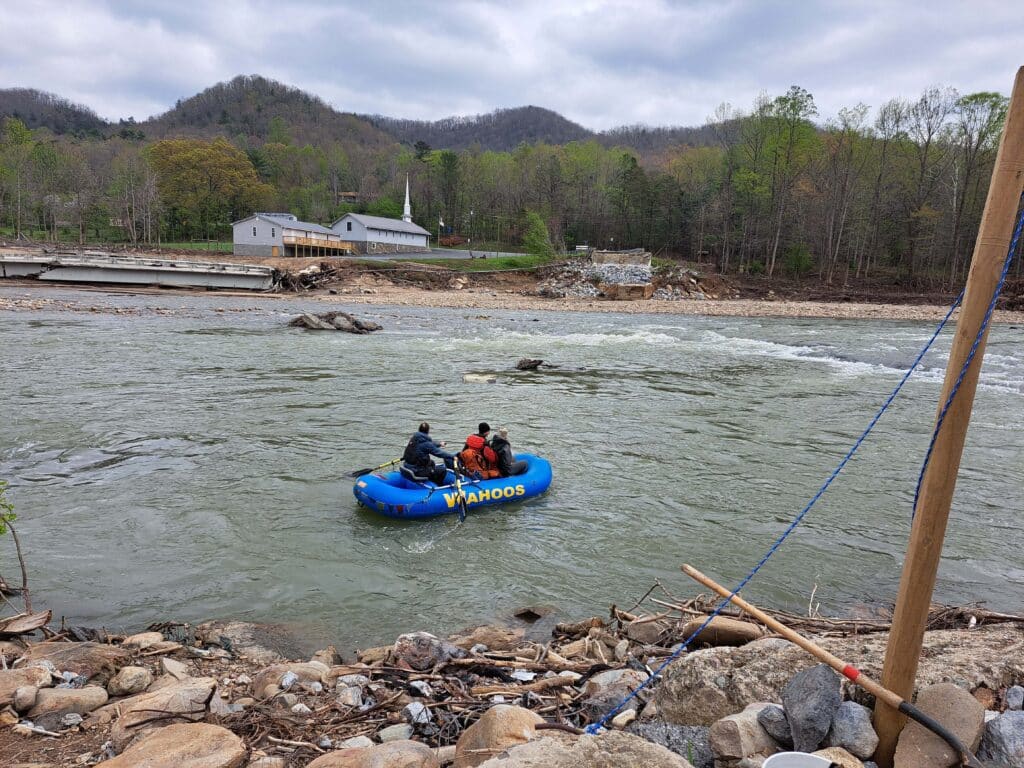

Ferrying Hope Across the Nolichucky

Erwin, Tennessee

For decades, the Nolichucky has been Erwin’s calling card—a wild waterway that has drawn rafters from across the country and sustained a tight-knit community of river guides. That all changed last fall when floodwaters destroyed access points, halted commercial rafting, and shifted the course of the river itself.

For Slayton Johnson, a river guide who purchased Wahoo’s Adventures months before the storm, it was devastating. “Helene took away access to the only river we operate on,” he says. “We had to pivot and get creative or go out of business.”

That pivot came in the form of a partnership with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. Backed by donations to the A.T. Resiliency Fund, Johnson and his small staff provided a free ferry service after the Chestoa Bridge—the A.T.’s main river crossing—was washed out. From 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. daily, guides rowed rafts across the Nolichucky, ferrying nearly 2,000 A.T. thru-hikers across the swollen river.

“It was massive for us,” Johnson says. “It kept a couple of our guides on payroll, kept money flowing through the business, and gave hikers a safe crossing.”

Other guides weren’t so fortunate. Mason Schmidt of Blue Ridge Paddling says his business shuttered the day Helene swept away about $2 million of infrastructure. A $515,000 state grant has helped with repairs, but with so much gone, Schmidt says they’re essentially starting from zero.

Matt Moses, owner of USA Raft Adventure Resort, faces a similar dilemma. “We’re completely shut down on the Nolichucky,” he says. “And the ripple effects reach far beyond us—to guides and drivers, to Airbnb hosts, to restaurants. The whole town feels it.”

But as access along the Nolichucky remains limited, other assets are carrying the town’s outdoor economy forward.

Located just a mile from downtown, Unaka Bike Park features more than 10 miles of trails and 700 feet of elevation change. When Helene tore through the region, its location on the leeward side of the mountain sheltered it from the worst winds, leaving only minimal damage. “We had trees cleared off within a couple of days, and every trail was rideable,” says Joseph Wigington, president of the affiliated nonprofit.

In the year since, the park has become a lifeline for Erwin—a place where locals and visitors alike can keep the spirit of outdoor adventure alive.

“The river will come back—probably rowdier than ever,” says Wigington. “Until then, our trails are here, and they’re helping keep the town together.”