Photo courtesy BRENDA WILEY

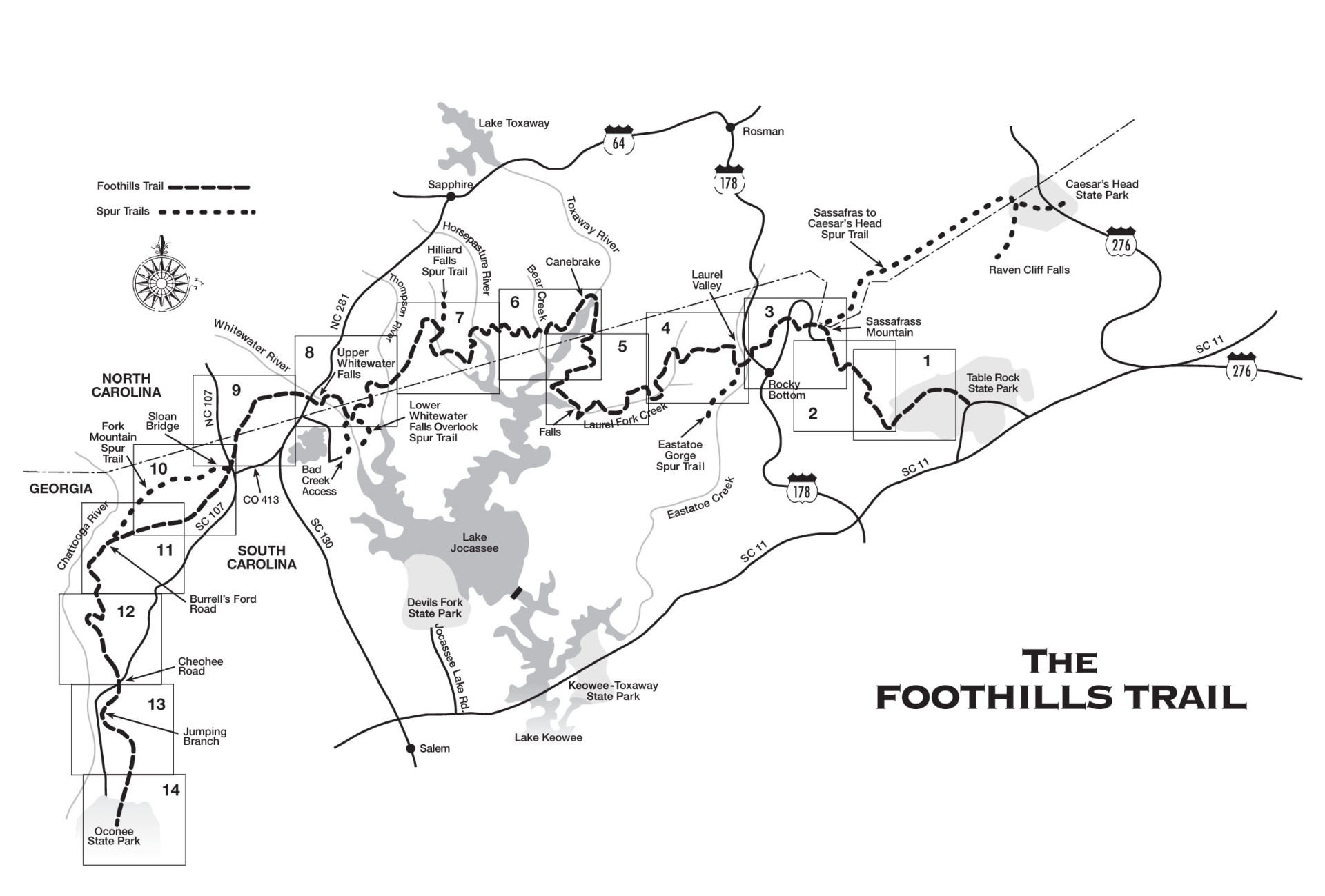

My pace picked up to a brisk trudge when I started to hear the roar of Carrick Creek Falls, at the eastern end of the Foothills Trail in South Carolina’s Table Rock State Park. More, even, than the usual post-trek treats—beer, real meal, real bed—I wanted a good soak in that chilly water. I’d underestimated the Foothills. I’d figured a thru-hike would be no problem for a recently transplanted Floridian because, after all, it’s just the foothills—not really the mountains, mostly in reputedly tame South Carolina. But by the end I was footsore and battered. I was exhausted. I was done.

And yet, even before slipping into the swimming hole beneath the falls, I realized that I wasn’t. Done, that is. Not if I wanted to walk all of the foothills. Why stop at Table Rock when it’s practically neighbors with Caesar’s Head and Jones Gap state parks, which together form the 13,000-acre Mountain Bridge Wilderness, home of some of the best trails in the state? The forests there are just as lush, the hills just as steep, the creeks and rivers just as clear and tumbling. And then there’s the name, Foothills, which fails to capture the drama and difficulty of the landscape, fails to give fair warning to hikers. The better, alternate term for the southern escarpment of the Appalachian Mountains is the one reportedly favored by Cherokees, the Blue Wall. That’s what it looks like from the flatlands, where it’s also clear that Table Rock is closer to the midpoint than the end. Nothing against the existing, 77-mile trail, which, according to the Foothills Trail Conference website, Backpacker has ranked as “one of the best long trails in the country.” It’s just that it could so easily be a little better, a little longer—about 90 miles. I can almost picture the thru-hike patch, because I already have the name: The Blue Wall Trek.

That wall defines the region’s climate, which defines everything else about it. Moist air cools with the sudden rise in elevation, releasing about 80 inches of rain per year. The resulting temperate rainforest supports a vast variety and abundance of plant and animal life, including the rare Oconee Bell wildflower and one of the densest black bear populations in the East. Rain, of course, also means rivers. The Foothills crosses and/or follows five of them and passes several spectacular waterfalls, including the 411-foot Upper Whitewater Falls. Four of these rivers flow into the famously clear and sparsely developed Lake Jocassee.

Despite all these attractions and Foothills’ stellar reputation, it’s hardly overrun. On a 20-mile day on my June thru-hike—a day walking among the column-straight trunks of tulip poplars and red oaks, crossing rapids on discrete but well-engineered bridges and regularly catching shimmering views of Jocassee—I encountered two parties of boaters and precisely zero other hikers.The trail climbs several ridges between river basins but only one real peak, 3,563-foot Sassafras Mountain, the highest point in South Carolina. The standard Foothills route heads southeast from there to Table Rock, a 10-mile stretch that on a clear day offers a spectacular view from a clearing below the summit of Pinnacle Mountain. But the day I crossed this bald was not clear and, in the mist, the fire-scarred landscape with its eroded trench of a trail reminded me of nothing more than a World War I battlefield. This stretch is being rerouted and the forest will quickly recover and ultimately benefit from last fall’s forest fires, said Heyward Douglass, executive director of the Foothills Trail Conservancy.

And I have to admit that the route I followed from Sassafras to complete the Blue Wall Trek, tracing the state line and therefore blazed alternately with Clemson University orange and University of North Carolina blue, is initially short on scenery and also shows the effects of the fires—wide swaths of charred understory and mazes of fire breaks. I must also admit that this stretch has already been designated as part of a Foothills spur that leads 14.2 miles to a trailhead on U.S. 276 in Caesar’s Head State Park.

But, unaccountably, the spur bypasses one of the park’s main attractions, 420-foot Raven Cliff Falls. About 12 miles from Sassafras, I turned right on the Naturaland Trust Trail and followed its Pepto-Bismol-colored blazes to the dizzying, deafening crossing on a suspension bridge over one of the fall’s main drops. From there, the attractions come along as fast as fence posts on a highway: the 120-foot-high cliff face known as The Cathedral, a deep valley shaded by mature hardwoods and speckled with wild hydrangeas, sparkling Mathews Creek. I pitched my tarp near the creek crossing—at a campsite reserved in advance because it lies within a state park—and in the morning was greeted by a Foothills-worthy, 1,300-foot climb on the Dismal Trail. A short spur at the top leads to the Raven Cliff Falls observation deck.

I walked on to the trailhead at U.S. 276 and crossed the road into Jones Gap State Park, which offers several good options for the hike’s last leg. I chose the 5.3-mile route that includes Coldspring Branch Trail, partly because it starts with a gentle climb over a hillside carpeted with ferns. Also, the Blue Ridge escarpment is all about water and the Coldspring trail—following its namesake creek and crossing tributaries—gives hikers a closeup, start-to-finish view of a mountain stream as it grows and gathers momentum before flowing into the Middle Saluda River. This brings the hike’s total inventory of landmark rivers to an even half-dozen. And though the competition is fierce, the Middle Saluda’s massive boulders, impressive drops, and inviting pools, might make it the most spectacular of the lot.

The final stretch along the river follows the historic path of the Jones Gap Road through the mountains. As I neared the park’s log-and-stone visitor’s center, I noticed the river widening and the gap’s walls sloping downward. I felt as if I had reached the natural end of not just of my hike but of a region of high, wild, and watery landscape, the end of the Blue Wall. I felt as if I deserved a patch.